Next in my series on lost Pittsburgh neighborhoods: Pipetown.

Pipetown early history

The area that was known as Pipetown in the 19th century was a valley that lay along 2nd Ave. between Boyd’s Hill (also known in those days as Ayer’s Hill, now known as The Bluff) and the Monongahela River. It was also bordered by a vanished stream called Sukes Run. The Monongahela terminus of the Pennsylvania Canal (see my previous blog post) was where Sukes Run ran into the Monongahela River.

Pipetown, also known as Kensington or Riceville, got its name from an early settler named William Price, who had a small shop there where he manufactured clay pipes. He was described as “an eccentric little gentleman” known for his quirky humor and his mechanical genius.

The neighborhood was a small, compact community that covered the area along Second Avenue from about the current site of the County Jail to Try Street. It was a rough neighborhood of machine and tool factories, slaughterhouses, breweries and laborers’ cottages and tenements. An 1826 directory listed, for example, two steam-rolling mills, a wire manufacturer, an air foundry, a steam grist mill and a “steam engine for turning and grinding brass and iron.”

For those especially interested in breweries, here’s a link to a good article about early Pittsburgh breweries. Scroll down to the section on Kensington brewers. Two breweries stood on the present-day location of the Allegheny County Jail.

1845 Fire

Pipetown was severely impacted by the fire in Pittsburgh in April 1845. The fire started on Ferry Street in Pittsburgh and the high winds that day rapidly advanced it east right through Pipetown. The fire was extinguished within the city limits by 7 p.m., but it continued to burn in Pipetown until 9 p.m.

The factories and tenements were quickly rebuilt. The residents of Pipetown may have been poor and rough, but they were tenacious and hard-working. In my previous blog post, I noted that historic Bayardstown included many small businessmen. Virtually all of the Pipetown residents in an 1869 directory were listed as puddlers, coke burners, teamsters and general laborers. Pittsburgh in the 19th century was a rough, dirty town, but it was also a place of rapid change and great opportunity. It is astonishing how far and how quickly some of the laborers rose from their circumstances.

Samuel Young, born in Pipetown, wrote his autobiography in 1890. In it, he describes being hired as a puddler’s helper in the Pipetown rolling mill owned by Church, Carothers & Co. The mill was destroyed in the 1845 fire, and he next got a job at another rolling mill in Franklin, Venango County. He soon got a promotion to being in charge of the “stock department.” He also started writing for the Conneautville Courier, and wrote a book as a serial for them. Then he was one of the workers who pitched in and bought the mill. From puddler’s helper to factory owner in the course of his adult life. And he wasn’t the only one.

William Tatnall

My favorite Pipetown Horatio Alger is William Tatnall Jr. William Sr. arrived in Pipetown in 1800 at age 6. He and his wife Ann were both born in London, England. William Jr., born May 4, 1825, went to work in one of the mills at age 9, when William Sr. died. At age 23, he was working in Kensington Roller Mills as a puddler. He was promoted to puddling supervisor and then to plant manager. In 1847, he married Susanna Rowland, whose father owned a coal works in Birmingham (present-day South Side of Pittsburgh).

Once he had some technical and management experience, and the necessary capital, Tatnall went into partnership with five other gentlemen (named Lindsay, Owen, Sample, Moody & Sellers). They opened their own rolling mill, Excelsior Mill, in Woods Run. The mill failed and Tatnall lost his capital.

Undeterred, Tatnall went back to work as a general manager of other mills in Western Pennsylvania: Schellenbergers Mills, Lochiel Iron Co., and Pittsburgh Forge & Iron.

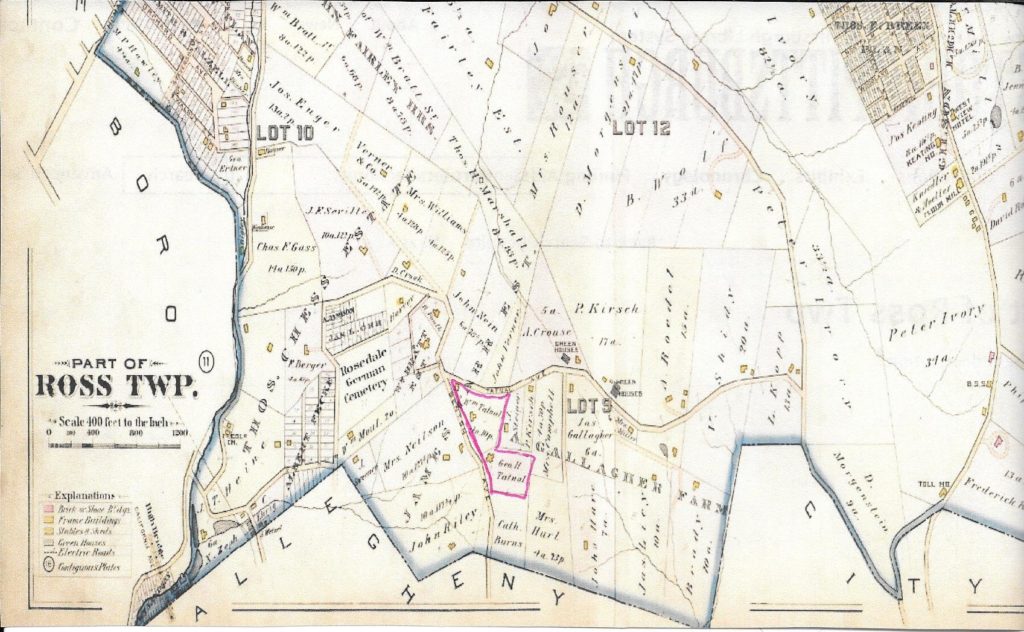

At some point, he bought a farm in Ross Township, and there he retired around 1904, aged 79. He later left the farming to his sons and lived in a home in Bellevue.

Tatnall outlived his wife and 4 of his 6 children. He was still living as late as 1914, and his biography in a 1914 directory of prominent Pittsburghers notes that his daughter Sarah was living with him at that time. The biographer also notes that he had been a long-time Republican but later in life was a Progressive and was known for his “very liberal views.”

I found an 1897 map of Ross Township that showed a William Tatnall farm and a George Tatnall farm adjacent to each other roughly where Benton Avenue and Tatnall Avenue intersected. George was one of William’s sons, and he died some time between 1904 and 1914. City of Allegheny Fire Department records indicate that there was a fire on George’s farm in 1904, but the records don’t provide details on the amount of the loss or whether anyone was hurt.

After that, the Tatnall trail goes cold. I found an Edna Grace Tatnall at Chatham College in 1909, but couldn’t establish what relation, if any, she was to William.

But I love Tatnall’s rags-to-(modest) riches story. His story of starting at the bottom and making it into the upper-middle-class is quintessentially American. He must have had some good luck, but he had his share of bad luck, too. What caused Excelsior to fail, for example? Did they start their business at the wrong time? Or did Tatnall choose bad partners? Did a big customer fail to pay? I could discover no details, but we do know that Tatnall dusted himself off and went back to work living his all-American story.

Pipetown today

Here are some shots of Pipetown today. It is still the site of some heavy industry including at least one rolling mill, and a lot of technology companies. It was also, of course, the site of the J&L Steel Mill in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Sources

http://www.pittsburghbrewers.com/styled/styled-5/index.html

http://www.pittsburghmetrofire.com/history.html

Genealogical and personal history of western Pennsylvania. Vol. 1

Municipal reports of the City of Allegheny for the fiscal year ending. 1904/1905