When we say something is Manichean, or someone has a Manichean view, we mean “black and white,” a very sharp distinction between good and evil, with no gray area. But where does the term Manichean come from?

When we say something is Manichean, or someone has a Manichean view, we mean “black and white,” a very sharp distinction between good and evil, with no gray area. But where does the term Manichean come from?

The Manicheans were a sect contemporaneous with early Christianity. My portrayal of Saint Augustine as an adherent of Manicheism as a young adult was based on his own admission in his Confessions.

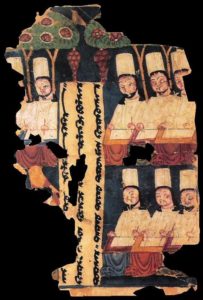

Mani (a term of respect meaning Light King, probably not his real name) was executed in Persia in 276. Similar to Christianity, his evangelists wasted no time in spreading his story throughout the Mediterranean, and Manichean missionaries were active in Carthage by 297. By Augustine’s time, the cult had adherents in Africa, Spain, France, Italy and the Balkans. It was known as far east as India, China and Tibet, and lasted for almost 1000 years in parts of the Middle East. Unlike Christianity, the Manichean cult remained illegal under the Roman Empire, and was hated and feared by Christians and Pagans alike.

Also unlike Christianity, whose central tenet is salvation by the Grace of Jesus Christ, the Manicheans believed that the enlightened elect could obtain godlike status by virtue of their own knowledge and actions. In this respect, the cult was a form of Gnosticism (the belief that salvation is obtained by acquiring special knowledge; some Christian heresies were also Gnostic in nature). The Manichean elect knew complicated secret prayers, practiced extreme fasting and were forbidden to own property, eat meat, drink wine, gratify any sexual desire, engage in trade, or engage in any servile occupation. “Hearers” like Aurelius Augustine had only to obey the Manichean Ten Commandments (similar to the Commandments familiar to Christians), pray 4 times each day and serve the elect.

The Manicheans were prolific writers, and we know the titles of many of their writings, but almost nothing has survived. From what little we do know, the Manichean theology seems like a confusing mess of demiurges, light particles, multiple creations, and a fire that will burn for exactly 1486 years to separate the light from the darkness. Yet, the Manicheans claimed to offer absolute rational proof of their theories, and insisted that phenomena in the physical world were demonstrations of the truth of their theology.

It’s easy to see why a bright young man like Aurelius Augustine, a passionate seeker of truth, would be initially attracted to such a cult.

Another central tenet of Manicheism was the notion that spiritual world is completely good (light) and the physical world is corrupt and evil (dark). This is the source of our current use of the term “Manichean” to mean a very black-and-white view. In the Manichean theology, Man can only hope to attain any goodness at all because a few light particles leaked into humanity at the time of the third creation. These light particles of our good selves are helplessly trapped in our corrupt physical bodies. This notion may also have appealed to young Augustine, who was so morally serious and having such a difficult time controlling his natural sexual urges.

Later in life, Augustine wrote a whole book entitled Concerning the Nature of Good: Against the Manicheans. Like Zoroastrianism and the temple religions of the ancient world, Manicheism failed the test of time. It lives on only in the descriptive term that is reminiscent of its strictly dual view of the natural and spiritual worlds.