When we crossed the Ohio River early one October morning, we just had to trust that it flowed there under the bridge. Dense fog shrouded the river, and I wondered how anyone ever navigated it before the era of bridges and electric lighting.

The first few miles of the National Road in Ohio looked very unpromising: thrift stores, decrepit housing, and an amusing flag featuring a much fitter and younger fantasy Donald Trump riding a dinosaur and firing automatic weapons with both hands at unseen enemies. It looked like the promised prosperity associated with the National Road had still not reached the state almost two hundred years later.

Pike Towns Along the National Road

Not until we reached St. Clairsville did we begin to see the impact of the National Road in Ohio. St. Clairsville was founded two decades before the National Road reached it, but it still looks like so many other “pike towns.” The importance of the road to the economic life of the pike towns can still be seen in the towns’ layouts: one main street, with a few cross streets and parallel back streets. In the nineteenth-century heyday of the National Road, these towns sprung up about ten to twelve miles apart – the distance that a stagecoach or wagon could travel in a day. Inns were often found on the crests of hills. Drover’s inns tended to be on side streets where livestock could be accommodated. Some towns were home to as many as five taverns. In larger towns, wheelwrights and blacksmiths made themselves available to perform repairs.

Many of the old pike towns have completely disappeared. Of the ones that remain, some are struggling, and others still prosper. But the basics are always the same. Retail shops, churches and historic houses along the main street. Often, in larger towns, a Masonic Hall on the corner. More churches, smaller shops and aluminum-sided early-20th-century homes on side streets. A gas station on the corner as you enter town, often now a Sheetz. And always a library. No matter how small the town, no matter how beaten down, there is almost always a library on Main Street, even if a very small one with limited hours. That fact alone gives me hope for our country.

A Pike Town Gallery

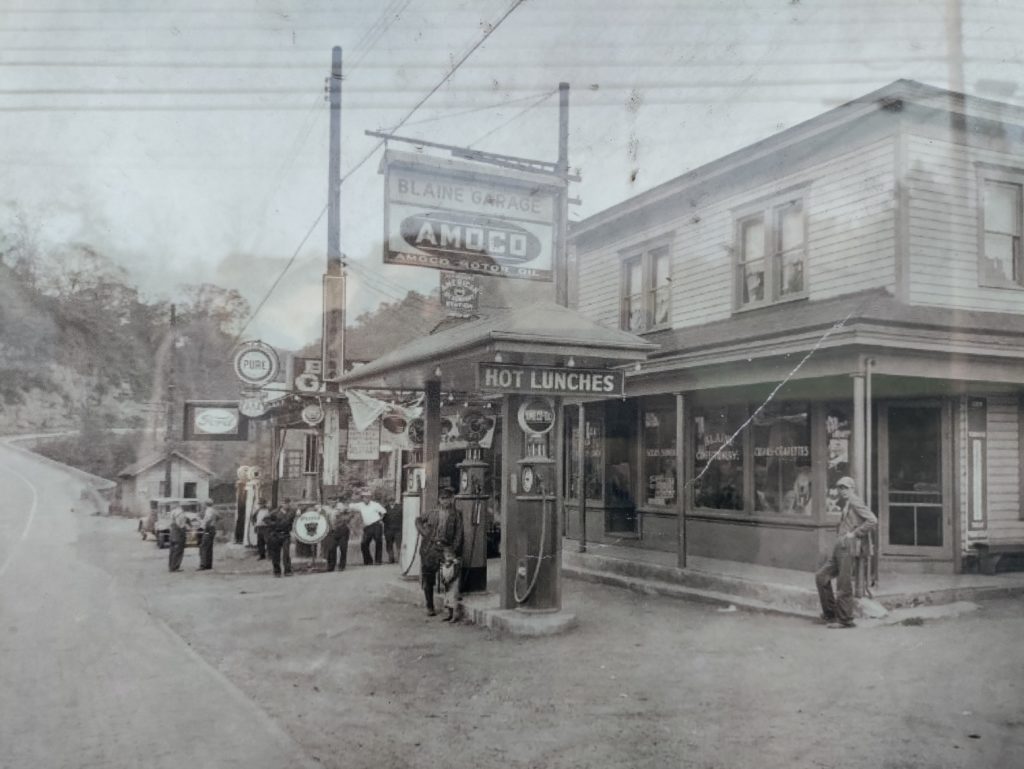

A sampling of Ohio pike town buildings: Above left, a scene from Blaine in the early 20th century. Above right, Saint Clairsville. Below left, the Red Brick Tavern in Lafayette. Below right, the Pennsylvania House Tavern in Springfield

The picture to the right is the 1870 Great Western School House near St. Clairsville. The grounds are so pretty; recess time must have been paradise

Our favorite Ohio pike town was Morristown, where they are making a real effort to restore their historic main street. They have completed research on the restored houses, and each one is marked by a plaque that tells you the name and occupation of the building’s pike-era resident. Unsurprisingly, many were tavern keepers and merchants. One is listed simply as “widow.” Others had occupations like blacksmith or wheelwright. The restoration process is uneven. Beautifully restored buildings stand right next door to decrepit wrecks. But the effort is very impressive, and I hope it will continue.

The Zane Grey Museum

One of the highlights of our drive through Ohio was the National Road-Zane Grey Museum. This small museum is a gold mine of information about the history of the road. Its collection includes a restored Conestoga wagon and impressive dioramas showing scenes from the early life of the National Road in Ohio: a tavern scene, road construction scenes, scenes from the early days of the automobile on the road.

At the museum, we also learned details about how the road was constructed. Using local farmers as laborers, builders made a sixty-foot cut for a thirty-foot wide road. The cut was 12-18” deep. Laborers then broke rock into three sizes. They laid the largest rocks as a road bed, covered by a layer of middle-sized rock, and topped that with gravel no bigger than 3”.

It’s not hard to imagine how rough that kind of road would have been! By the early twentieth century the road was repaved with brick. In 1925, the road was widened, straightened, rerouted in some places, and got its Route 40 designation. Asphalt paving started in 1932.

Our Drive Through Western Ohio

The terrain of Ohio changed gradually as we drove west. Eastern Ohio features wooded hills and valleys. The farming there was limited to subsistence agriculture on small plots on ridges or in valleys. Western Ohio is the place for large-scale farming, thanks to the flatland formed by the Illinoian and Wisconsin glaciations. We drove past miles and miles of cows and corn and enormous grain silos. In the big skies above, geese made their way south and huge flocks of starlings gathered.

Late in the day, we found Ohio’s Madonna of the Trail. We’ve seen several of the Madonnas now, and they never fail to move me. The raw-boned mother in her plain dress and sturdy boots, one child in her arms, another hanging on her skirts, striding hopefully into an unknown and perilous future. Many years ago, when I was in sixth grade, I read a book called A Lantern in Her Hand, about a pioneer mother, and I loved it so much that I’ve read it many times since. We often say that George Washington was the father of our country, but these unnamed women were truly its mothers.

After the Madonna, and a brief hike, it was on to Indiana, the topic of my next post!

Sources

Schneider, Norris F. The National Road Main Street of America. Columbus, Ohio: The Ohio Historical Society, 1975.

Harper, Glenn and Smith, Doug. The Historic National Road in Ohio. Columbus, Ohio: The Ohio Historical Society, 2010.