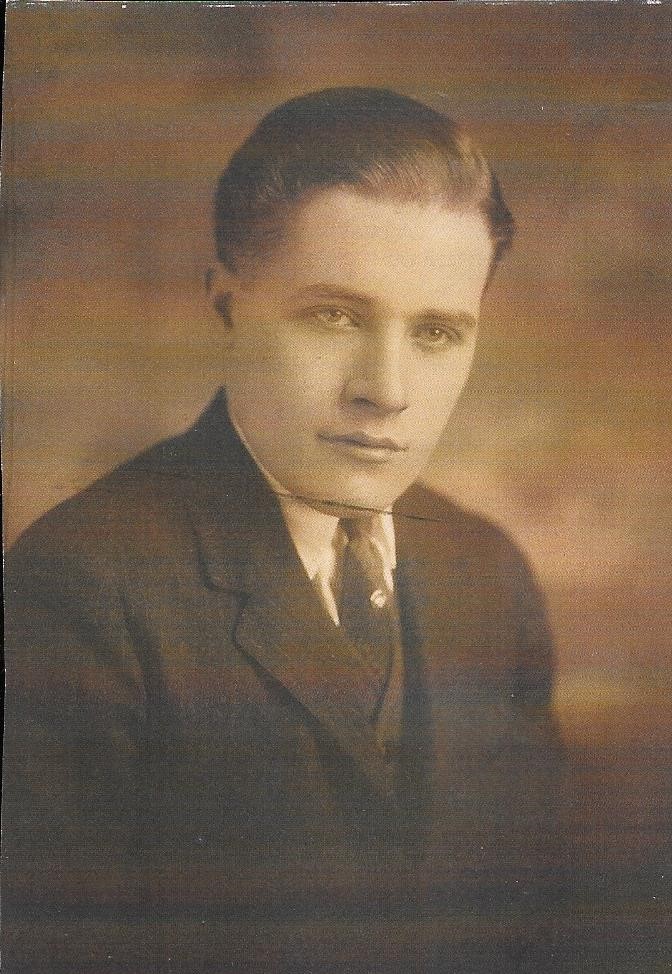

After I posted the short-story about my grandmother, I remembered this story that I wrote about 15 years ago, based on my grandfather’s very short service in World War I. In this story, I imagine my grandmother as having a teenage crush on the older Nock Yaggi, and I hint at a future for my grandparents very different from the lives they actually lived. This story has never been published before…

Nock shouldered his way through the crowds to approach Mike’s coffin. He wouldn’t see Mike, of course. Mike’s body was buried somewhere France. But atop the coffin stood a picture of Mike in his Doughboy uniform, taken right before he shipped out. Elaborately framed in leaf-and-flower carved gilt, draped with black ribbon, Mike gazed defiantly at the viewer frowning a little as if skeptical that his glory days would be brief, that his life would shortly end in a dusty trench under a foreign sun.

The atmosphere at McDermott’s Funeral Home was almost festive on this hot August night in 1918. Bodies were packed elbow-to-elbow, smelling of sweat and of suppers of cabbage or garlicky sausage. The men’s necks glistened with perspiration over their starched collars, and the girls’ frothy white dresses wrinkled from the press of the crowd. The matrons forming a protective circle around Mrs. Yerkovich discreetly dabbed at their faces with handkerchiefs to pat away the sheen of sweat. Everyone talked at once, in low voices, of the first local boy to fall in the Great War.

Nock knew it wouldn’t be polite to admit it, but he envied Mike’s hero status. At least he got to go. Almost everyone except Nock got to go. Mike, Frank Loeffler, and Leo Braun all enlisted the day after high school graduation. Even Leo’s younger brother, Karl, was allowed to skip his last year of school and sign up. Only Nock was forced by his family to wait until his 18th birthday, still two months distant.

They just wanted to keep him a slave in the family furniture business, was what Nock had been a slave to that furniture store for as long as he could remember. As soon as he could hold a broom, he was sweeping the sidewalk in front of the store. Every spring, he painted the wooden stoop, and his parents had insisted that he take the business course in high school so that he could keep the books for the store when he graduated. He had spent his summer sitting on a stool in the office behind the store, adding up sums in a ledger, unspeakably bored, the electric fan solemnly shaking its head back and forth, back and forth, as if forbidding him to imagine any other life. Once every morning and once every afternoon, he stepped out into the alley behind the store for a cigarette. If he wasn’t interrupted by a delivery, or by a neighbor or workman taking a shortcut through the alley, he could daydream undisturbed by debits and credits.

Nock wasn’t sure where he was meant to make his life, but it was surely somewhere other than Yaggi & Junker Furniture in McKees Rocks, Pennsylvania, four miles down the Ohio River from Pittsburgh. Did no one but him see the irony of being in the furniture business with a family named Junker? When Nock pointed this out to Sylvester, his brother just rolled his eyes and said, “Yeah, Nock, real funny. You oughta be in vaudeville.” Sylvester, 24 and married, was humorless as far as Nock could tell. Well, he could work in the furniture store with the Junkers for the rest of his life if he wanted. Nock had bigger plans. Well, not plans exactly. He didn’t know for sure what he wanted to do, but he knew it wouldn’t have anything to do with ledgers and that it wouldn’t happen in McKees Rocks.

Maybe he belonged in California, working for the movies, or on a ranch in Montana, or in Africa hunting wild game like Roosevelt. Best of all would be to join his friends in France, fighting to make the world safe for democracy. Mike had gotten a leave before he shipped out and Nock’s heart twisted with envy of the snappy Doughboy uniform, and the gun. Working in the furniture business had given Nock an appreciation for fine wood, and Mike’s Springfield rifle was one high-quality article: glossy and substantial. Nock itched to heft it to his shoulder and hook his index finger around the satiny steel trigger, but Mike wouldn’t let him try it out. He said he had orders not to let civilians handle his equipment, but Nock was pretty sure he was just showing off.

After standing solemnly before Mike’s picture for a respectful amount of time, he began to make his way back through the crowds, so that he could slip into the alley and have a smoke. There was that silly little Mary Grant watching him. The minute he’d walked into McDermott’s, she came bouncing right up to him, bold as a stallion, “Hi, Nock!” with a big sassy grin on her face, swinging her head so that the braid down her back tossed. For crying out loud, she was maybe 14, didn’t even put her hair up yet. Anyway, if she had her eye on him she should just forget it for a lot of reasons. First, Nock doubted that he would ever get married. Second, if he ever did get married, first he intended to see the world, starting with France, where he was pretty sure that buxom French mademoiselles were happy to be kissed or more by the sharply-dressed American soldiers come to save their country from the Huns for them.

Nock had escaped to the alley and lit his cigarette and was just enjoying himself imagining the red wine and the mademoiselle and what her breasts might look like, when he felt a tap on his left shoulder. He turned his head in that direction, but felt a swift movement behind him and spun his head the other way to see Mary Grant’s grinning face behind him on the right.

She laughed. “Hi, Nock Yaggi.”

“Hi.” He made only the briefest eye contact and inhaled some tobacco, hoping to give her the hint to go away.

Instead, she leaned against the wall behind him, one leg bent, with its foot flat on McDermott’s wall. “Shame about Mike.”

“Yeah. You’re going to get your dress dirty leaning on that wall.”

“I don’t mind. It washes.”

“Free country, I guess.”

“Well, anyway, he was a hero and all.”

Nock tossed the remains of his cigarette across the alley. “Yeah. Well, I’m going as soon as I turn 18.”

“I though you were already 18.”

“October 10. I’m signing up that very day. My parents can’t stop me once I’m 18. I’m not so sure I’ll ever come back to McKees Rocks. I’d like to see what it’s like in New York City or maybe out west, after France. Or maybe I’ll even stay in France while after the war. I don’t know.”

“Oh, France. I’d just love to see France.”

He glanced over at her. “Well, you wouldn’t like it much now. Men shooting at each other across barbed wire. It’s no place for a little girl.”

Mary’s freckled cheeks flushed. “I’m 15, you know. Anyway, I’m talking about Paris, and I’m talking about after we win the war. And first I’m going to New York to sew costumes for the stage. Maybe I’ll even go out west to Hollywood and sew costumes for the movies.”

“Well, that’s nice.” He tapped out another cigarette and lit it, looking straight ahead and moodily blowing the smoke out of his lower lip.

“Could I try that?”

“What? Smoking?”

“Yes.”

Nock glanced around the alley. “What do you want to do that for? You’ll just get in trouble. Nice girls don’t smoke.”

“I just want to see what it’s like.”

He glanced both ways again and then passed her the cigarette. “Don’t inhale too deep the first time. You’ll get sick.”

He watched her anxiously as she inched the cigarette towards her lips and hesitantly sucked. She immediately choked and began to cough.

“See? I told you,” he said.

She held the cigarette away from him, stifling more coughing. “No, wait. Let me try it again,” she gasped.

“You’ll get sick,” he insisted.

Mary ignored him and inhaled again, turning away from him. This time, she emitted only one stifled cough.

She passed the cigarette back to him. “I just wanted to see what it was like.”

“Well, it’s not for girls. You know, New York City’s really no place for a girl all by herself either. What do your parents say about that? Where would you live?”

“They have hotels where the girls live who work on the stage. They all live together like sisters.”

“Oh. It’s like that out west if you work on a ranch. All the guys bunk in together. I might do that. Or I might go to work in the movies, too. I know bookkeeping, so I think I could do bookkeeping for a movie company, just to get my foot in the door, then maybe they’d let me do something more interesting.” He had gotten this idea a minute ago, when Mary talked about sewing for the movies.

“That’s a good idea.”

“Mary?” Once of Mary’s skinny friends, a girl in a black and white sailor dress, poked her head out the door into the alley. “Your mother’s getting ready to leave. She’s looking for you.”

“I have to go,” Mary said. “Maybe I’ll see you around before you go to France. Good luck.”

“Same to you.” He finished his cigarette and went back in to pay his respects to Mrs. Yerkovich.

Nock counted backwards from October 10 and marked on his office calendar the number of days until his 18th birthday. Monday through Saturday, from 9 a.m. until 6 p.m., he perched on his stool in the furniture store office scratching in the books, taking his cigarette breaks in the morning and afternoon, and walking home to have lunch with his parents. He tried to win a little respect from his father and brother by sharing his modern ideas about the business. For instance, why couldn’t they sell furniture on credit to some customers? Nock thought he did a good job of showing that, if they charged a monthly fee for the credit, they would actually make more money on every piece of furniture that they sold. “We’re the furniture store, not the bank,” Sylvester said dismissively. His father and Mr. Junker didn’t think that people should be encouraged to go into debt. They shouldn’t have the coat rack or the armchair until they had saved the money to pay for it. What about electric appliances? Couldn’t they look into adding electric appliance to their stock? Electricity was in almost every home now, and people were crazy about electric vacuum sweepers and the new electric iceboxes. They could make a lot of money selling electric appliances, Nock argued. His father calmly explained to him that they knew furniture, that was their business; they didn’t know anything about electric appliances. Nock felt like screaming at them, Well, then, find out! Nock wanted to scream, just in general, a good bit of the time. The whole world was changing, interesting things were happening, and he was trapped in the one place where nothing important was happening and nobody wanted anything to change.

Weekday evenings after dinner, Nock stayed home and caught up on the war news in the newspaper, then settled down with National Geographic or Popular Science. Sometimes on Friday or Saturday evening, he went to the movies or a vaudeville show with some fellows who were still in high school. One Saturday in September, he met Larry and Bob in front of the Roxian as usual, but Larry greeted him with, “No movie tonight, Nock. Something more interesting planned. You like ragtime, right?” When Nock nodded, Larry continued, “Well, there’s a new kind of music you got to hear, then. It’s called jazz. It’s like nothing you ever heard before in your life, Nock. They play it at some of the clubs in Pittsburgh.”

They waited for some more of Larry’s and Bob’s friends on the corner, then took the streetcar to Pittsburgh. Nock was surprised that Mary Grant and some other girls were among the group. In Pittsburgh, they transferred to another streetcar that took them into the Hill District east of the city center, a neighborhood of poor lighting and drooping, unpainted tenements populated by Syrians and Negroes. The club was claustrophobic with tobacco and another sweet-smelling smoke that Larry said he thought was called “hemp.”

They could barely see the small corner stage where a quartet of Negroes set up their instruments. For the next hour, Nock felt as far away as he had ever felt from his white-painted frame house on Second Street with its picket fence and his mother’s hollyhocks. The music felt dangerous. It wrapped itself around you like a snake, like the curling smoke from that sweet-smelling hemp. It got inside you and got your heart racing and your skin tingling, but at the same time you felt too relaxed to move. Nock was acutely aware of Mary Grant’s freckled arm a few inches from his, imagined that the very tips of its pale, fine hairs were yearning toward the hairs on his own arm. A few couples danced in the small space between the stage and the crowded tables, moving in a sinuous rhythm that Nock was embarrassed to watch. Towards the end of the set, a pretty Negro girl in oiled, marcelled waves and a short dress that looked like it was pasted on her wet, sang a few numbers in a husky lisp.

They were back on Broadway Avenue in the Rocks by 10, had walked the girls home by 11, and congratulated themselves on getting away with an adventure that would have scandalized their parents.

On Sunday, the Yaggis went to 10:00 Mass, then had an early dinner, with Sylvester and his wife Margaret in attendance, and then the endless dull Sunday afternoon stretched ahead. The day after the outing to the jazz club, Frederick Yaggi called Nock into the back parlor after Sylvester and Margaret left. Nock’s father was a square man, short, broad of shoulder and growing broader of waist. His complexion was florid, his hair the silver blond of a winter sun. Although born in the United States, he retained traces of his parents’ German accents, an embarrassment in these times, Nock thought.

His mother was already sitting in the parlor, twisting her handkerchief. Frederick sat down and gazed at his son sternly for a few long seconds. Nock’s heart began to flutter.

“I spoke with John Pfeffermann at church, Norbert, “Frederick began, “and what he told me was distressing to me.” Nock had been called Nock since babyhood. To be called by his given name of Norbert could only mean bad news. He remained silent.

Frederick continued, “Did you and Lawrence Beck and some other boys escort some young ladies to a Negro club in Pittsburgh last night?”

Nock kept his eyes locked with his father’s, afraid to look at his mother. “Yes, sir.”

“Mr. Pfeffermann makes deliveries to these places on weekends,” Frederick explained. “He was very shocked to see you young people in such a place. Do you have an explanation?”

Nock felt himself flush. “We wanted to see something more interesting than just another movie. We wanted to go someplace more interesting than the Rocks for a change.”

“You are not to go to such a place again,” his father said. “And you are certainly never to take a young lady to such a place.”

“Father, we were just listening to music. It was something really different and exciting. I – “

“Do not argue with me, Norbert. These places are not safe for nice young people. I expect to be obeyed.”

“Yes, sir. May I go now?” Nock felt a lump rising in his throat.

“Yes.” His father waved a hand as if to brush him away.

Nock left the house and walked up to the end of Chartiers Avenue, fuming. A fellow couldn’t do anything around here without being found out. Everything you did was watched and controlled and commented on. You couldn’t decide anything for yourself, not even what you did for fun or what music you listened to. He might as well be in prison.

He passed sagging Corny Mann’s Saloon, and continued up the hill through the cemetery. He stopped at Mike’s gave and tried to feel sorrow, but all he could feel was anger at his father and the sense of Mike’s being gone, just like he had been since he enlisted, like the other fellows were gone. Just not stuck in the Rocks like Nock. It was hard to get the sense of Mike never coming back. Maybe it would have been different if he’d seen the body in the coffin

Still full of rage and nervous energy, he strode back down the hill until he found himself at the river. It was the first cold snap of fall, with a wind that blew away the burnt-sugar smell of the coke ovens and the ashy smoke from the factories. Nock never minded the fog and smoke and odors from the mills along the rivers. To him, it was the smell of power and prosperity. It meant that fellows could find work, and machines could be made and the war won. It was a visible flexing of American muscle. He stood for a while and watched the tugs pulling the broad, flat barges down the Ohio, laden with hills of ebony coal or neat rows of timber or steel bars The railroad tracks along the river clattered with their burden of freight cars carrying corn from Illinois, cotton from Alabama, tanks and trucks to the coast for shipment to France. Everything and everyone except him seemed to be going somewhere else. He was marking time. But not for long. His birthday was nine days away.

His father kept him at the office late the night before his birthday for a man-to-man talk. Frederick solemnly fixed his small gray eyes on his youngest son. “Do you truly understand what you’re about to do, Norbert?”

“Yes, Father.”

Frederick shook his head. “I’m not sure you do. I’ve spoken with the Loefflers and the Yerkoviches and others. The letters that they receive from their young fighting men do not make a pretty picture.”

“I can read, Father. I know about the trenches and the gas.”

“The war has turned in our favor. I believe that it’s about to be won, with or without you. Why risk your life?”

“That’s just one more reason to sign up now, before I miss it altogether!”

Frederick sighed and removed his glasses. “Your mother is very distraught.”

“I know, Father, but I can’t help that. It’s my life. I have to be able to make my own decisions. I’m not going to die in the war. I know it.”

“A million young men already in their graves thought the same.”

Nock was annoyed to find himself near tears. “Well, I know I’ll die of boredom if I have to stay here much longer!”

Frederick gazed at his son in silence for a few seconds. “Your mother pleaded with me to forbid you to do this thing. That I cannot do. I see that you are determined. So!” He slapped his ham-hock thighs with his hands, then reached forward and placed a hand on Nock’s shoulder. “God bless you then, son. You will be in our prayers every day.”

Nock went the next day and signed up at the recruiting station on Chartiers. Only a week later, his father and Margaret saw him off at the railroad station in Pittsburgh. Sylvester stayed back and minded the store with Mr. Junker, and his mother had taken to her bed in distress.

Margaret hugged him, and his father clapped him on the shoulder and wished him Godspeed. “I’ll write,” Nock promised as he hopped into the train car. His heart was light as the train pulled out of Penn Station, leaving behind the sullen, oily Ohio, the little frame houses clinging to its hills and bluffs, and the spewing factories sprawled on its flats.

He spent the next four weeks in greasy New Jersey mud that he was sure couldn’t be any worse than the muddy trenches of France and Belgium. He did pushups in the mud, jumping jacks in the mud, five-mile runs in muddy boots. He stood, knelt and lay in mud for rifle practice. Cold rain dripped from the metal brim of his helmet. He sat at chow in his sodden wool uniform, eagerly scooping up plate after plate of gristly meat and lumpy potatoes, and his naturally thin frame began to fill out He collapsed onto the creaking, musty bunk right after dark and fell instantly to sleep, only to be wakened in icy darkness what seemed like seconds later, by a tinny reveille. He complained along with the other fellows, just to fit in, but secretly he felt as if his real life had finally begun.

Mary Grant somehow got his address and wrote him a letter. One rainy Sunday when he didn’t fell like playing cards with the fellows and he’d already written to his family, he decided to answer, just a few words.

Dear Mary,

Well, you asked what Basic Training is like and I can only tell you that it is work, work and more work. We do exercise and rifle practice from 5:00 in the morning until it gets dark around 6:00 at night. The food is awful, but we work so hard that we are hungry enough to eat plenty of it.

The fellows here are from all over the place. It’s funny that a lot of them feel the same about their hometowns in West Virginia or New York that I feel about the Rocks: it is a fine place to be from, but not to stay in. A lot of us feel like we’d like to see some of the world and have some adventures, and I guess we’re about to do that. We should be shipping out for France around the first of January. I don’t know if they’ll let anyone go home for Christmas or not. I have to admit I would like to come home one last time before we ship out, but we’ll see.

Sincerely,

Norbert Yaggi

He thought he’d walk to the exchange to mail it right away, but just as he was pulling on his boots, Lefty Liguori burst into the barracks. “Guys! Guys! Guess what! The Kaiser just surrendered!” – only Lefty was from the Bronx so he said “the kaisah just surrendahed.”

The barracks suddenly stirred. Fellows dropped their cards, their newspapers, their fountain pens, and crowded around Lefty. “You don’t say!” “Where’d you hear it?” “Kaiser heard we was coming and knew he better give up!”

Nock stayed on his bunk with one boot on, apart from the crowd. Maybe it wasn’t true.

But Lefty yelled over the milling heads. “Sweah to God! I know the guy in the telegraph room. He went to school with my brothah. He told me. The wah’s ovah!”

They were mustered out the very next day, told to line up in their civvies at the quartermaster’s to get their pay for the four weeks and their train tickets home, and hand in their rifles and uniforms. For a bunch of fellows who talked big about being glad to be out of their little hometowns, Nock noted grumpily that everyone except him seemed pretty excited and happy. The guy in front of him, Lester Martin, kept babbling about getting hired back on in the coal mine and marrying his girl as soon as he got back to West Virginia. There was a restless high-spiritedness in the air.

When Nock reached the sergeant’s desk and was handed a ticket to Pittsburgh, he asked, “Um, say…is there any way I could get a ticket to somewhere else instead?”

“What are you talking about? Ain’t you from Pittsburgh?”

“Well, near Pittsburgh, yes, but I was wondering if I could just go somewhere else.”

“You can go any place you want, soldier, but not at the expense of the U.S. Army. You come from Pittsburgh, that’s where we send you back to. Now move along: some other people is anxious to get home. Next!”

They were transported from Fort Dix the same way they’d come in: in the backs of canvas-covered trucks leaking rain. Then came the wait at the station for the train to New York City, from where they would scatter like billiard balls to their various dull homes.

The train to New York was warm, and cavernous Grand Central Station even warmer. The smell of hot, damp wool lay in Nock’s nostrils as he scanned the schedules for the next train to Pittsburgh. Festive red, what and blue bunting hung over his head, and echoing voices formed a constant background roar.

He stared at the schedule without really seeing it, waving his ticket absently. His eyes wanted above the schedule, to the map of the United States. What had the sergeant said? “You can go any place you want, solider.” Just because he had a ticket to Pittsburgh didn’t mean that he had to use it, and he had his four weeks’ pay.

He approached a ticket window. “Can I trade in this ticket to Pittsburgh?”

The clerk stared down his nose at it through half-glasses. “Nope. Military issue. Can’t trade this one in. Sorry, fellow.”

“Well, then, how much for a ticket to…” Nock thought for a second. “California?”

“Where in California?”

“Well, say Los Angeles. Isn’t that where they make the movies?”

“First class or budget?”

“Better say budget.”

The clerk consulted his price list. “Twenty-two dollars.”

“I’ll take it.” Nock pushed two twenties toward the clerk, more than half of his four weeks’ pay.

“Going to be in the pictures, are you?” the clerk asked.

“Something like that,” Nock replied.

“Good luck to you, fellow.”

“Thanks. When’s it leave?”

“On hour from now. 7:00. Track 12.”

“Thanks.”

Nock took his ticket and his change. He’d write to his family from the train. Maybe he’d write to Mary Grant, too, to let her know that he got out of town in spite of the Kaiser, give her a little hope. As he passed a trash can, he dropped the Pittsburgh ticket into it, and kept moving.