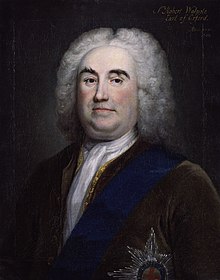

He was called The Great Commoner but ended life a Lord. HIs government positions ranged from a cornet in the Army to Lord Privy Seal to Prime Minister to Groom of the Bedchamber (not as sexy as it sounds). He suffered from severe gout starting at a very early age. And the greatest city in the world — OK, in the United States; oh, all right, the greatest city in Appalachia – bears his name. I’m talking about William Pitt the Elder, First Earl of Chatham.

The Pitt family

The origin of the Pitt family fortune comes from a gigantic diamond discovered by Pitt’s grandfather Thomas Pitt while he was governor of Madras in India. Thomas Pitt sold the diamond to the Duke of Orleans for the equivalent in 2021 USD of more than twelve million dollars. More than enough to put his son Robert in Parliament as a Tory MP from 1705 until 1727.

William Pitt was Robert’s second son. That meant that his older brother, another Thomas, inherited the Pitt estate. William had to do what most younger sons did in eighteenth-century Great Britain: serve in the church or the army. Pitt chose the army, obtaining a cornet’s commission in the King’s Own Regiment of the Horse. But he never saw battle or left Great Britain. Bored, he ran for Parliament and was seated in 1735, though still an army officer.

The Great Commoner as a young Patriot

Although his father had been a Tory, Pitt joined a Whig faction called the Patriots. They were critical of Prime Minister Walpole’s government. In particular, they were eager for glory and thought Great Britain should enter the War of Polish Succession. Ever hear of that war? Me neither, until exactly today. That should tell you how little it was worth the loss of British lives and treasure.

In my opinion, Walpole had the better position when he said “There are fifty thousand men slain in Europe this year, and not one Englishman.” By staying out of war, Walpole also managed to reduce both taxes and the national debt.

The Patriots did badger the government into a mini-war with Spain in the late 1730s. They were incensed that, when the Spanish caught British smugglers, they treated them badly. That war did not go well for Great Britain and was more or less abandoned. So, our friend Pitt was wrong about a lot of things early in life, as so many of us are.

Pitt’s political rise

Through his friend the Prince of Wales (the future George III), Pitt gained the positions of Vice Treasurer of Ireland and Paymaster General in 1846. Here, he performed exceptionally well. It was common for men in the paymaster role to skim off a commission for themselves in addition to their salary. Pitt refused to do that. His honesty earned him the love and respect of the common people of Britain, and his nickname The Great Commoner.

Pitt had his political ups and downs for the next decade or so. But, by 1757, he was Secretary of State and Leader of the House of Commons. He again proved his worth by revamping the British strategy in the Seven Years War. Under Pitt’s guidance, Great Britain allied itself with Frederick II of Prussia. Frederick’s little Prussian force managed to keep French forces pinned down in Europe. That gave Great Britain the freedom to successfully attack the French elsewhere in the world: West Africa, the Caribbean, North America. The British gained Pittsburgh, Guadeloupe and Quebec in 1758 and 1759. With their victory in Montreal in 1761, the war was essentially over. Pitt claimed to have “won Canada on the banks of the Rhine.”

Pitt and the Americans

But success came at a price. The war was costly for Great Britain. As every American school child knows, the British attempted to tax first stamps and then tea, to pay for their expensive North American victory. The American colonists, of course, objected violently. Pitt was an ally to the colonists, arguing in Parliament against the stamp and tea taxes. Later, as the War for Independence loomed, he tried unsuccessfully to convince Parliament to make concessions to the rebellious Americans and correctly warned that the colonies could not be held by force.

Pitt and Pittsburgh

William Pitt the Elder died at age 69 on May 11, 1778. His legacies were his status as one of Great Britain’s most highly-regarded statesmen; his son, William Pitt the Younger, who became Britain’s youngest Prime Minister in 1783 at age 24; and, of course, the city that bears his name.

Following his victory at the Forks of the Ohio River in November of 1758, General John Forbes wrote in a letter to Pitt dated November 27, 1758, “Sir, I do the honour of acquainting you that it has pleased God to crown His Majesty’s Arms with Success over all His Enemies upon the Ohio…I have used the freedom of giving your name to Fort Du Quesne as I hope it was in some measure the being actuated by your spirits that now makes us Masters of the place.”

When the city of Pittsburgh was officially chartered in 1816, it adopted a seal based on the Pitt coat of arms. The original seal was lost in the 1845 fire and had to be recreated from memory. The three gold coins, called bezants, are loosely based on Byzantine coins, and symbolize honesty. The blue and white checks are the Pitt family livery colors. The Castle simply symbolizes a city. Pitt’s city.

Sources

Lorant, Stefan. Pittsburgh: The Story of an American City. Lenox, MA: Authors Edition, Inc., 1988.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Pitt,_1st_Earl_of_Chatham

https://www.u-s-history.com/pages/h1182.html