The first known Black resident of Harpers Ferry, a slave of Robert Harper, came to the area with Harper when he bought squatter’s rights from Peter Stephens in 1747. As the river town grew into an industrial powerhouse, the population naturally expanded. By the time of John Brown’s raid in 1859, ten percent of the town’s three thousand residents were Black, about evenly divided between enslaved and free.

And, after the Civil War, Harpers Ferry became the home of an institution that educated thousands of Black students over a period of eighty-eight years.

The Beginning

At the end of the war, more than thirty thousand newly-freed Black people lived in the Shenandoah Valley. It isn’t hard to imagine how eager they must have been to make the most of their newfound freedom. But most were illiterate. Until the end of the war, it had been illegal to teach any Black person to read or write.

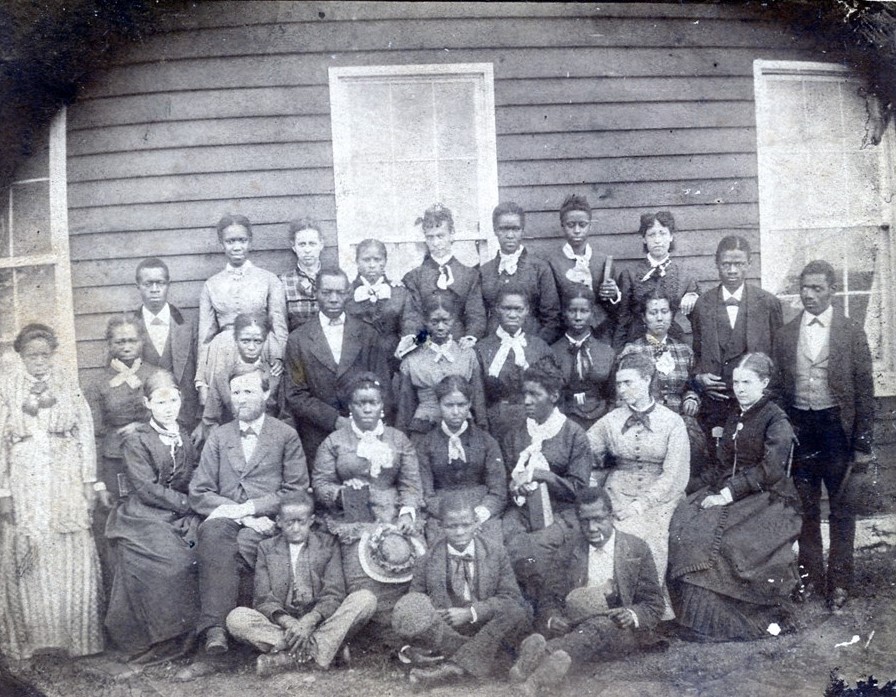

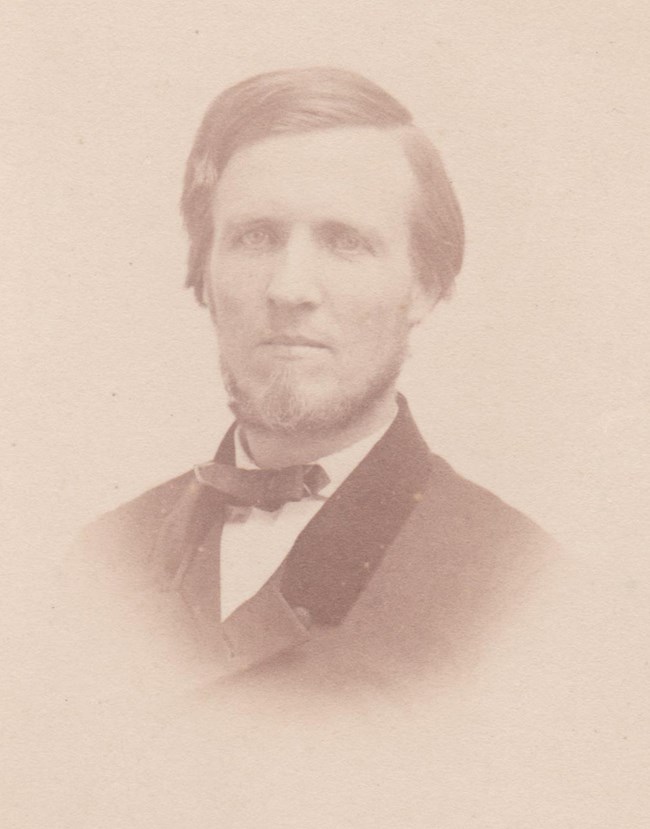

Schools sprung up all over the South, many of them church-affiliated. The little school in Harpers Ferry was one of many created in the eastern panhandle of West Virginia, by Freewill Baptist minister Nathan Cook Brackett, in cooperation with the Freedmen’s Bureau. It started by educating adult freed slaves alongside their children. But most of the adults gave up in frustration. Contemporary sources described the first class of nineteen formerly enslaved children as “poorly clad, ill-kept and undisciplined.”

But then the school came to the attention of a wealthy Maine abolitionist, John Storer. Storer offered a $10,000 grant to the school under certain conditions. The school must admit students regardless of color. It must make plans to become a degree-granting college. And it must raise a $10,000 match within one year.

Under Brackett’s determined leadership, the school managed to raise the $10,000 with only one day to spare, thanks to a combination of donations, government funding and multiple mortgages. Thus, Storer College was born in 1867.

Early History of Storer College

The school struggled at first. Until 1869, the war-damaged armory paymaster’s house (Lockwood House) served as both the schoolhouse and the dormitory for teachers and resident students.

White residents resented the education of their Black neighbors. Students and teachers reported regular harassment. Vandals damaged the school buildings. Local newspapers slandered Brackett, and local politicians made efforts to close the school.

Brackett’s daughter told a possibly-apocryphal story of a time when a mob of whites confronted him with lynching on their minds. According to the story, a Confederate veteran rescued him and declared that the mob would not touch Brackett without killing him first. Apparently, during one of the many battles that took place near Harpers Ferry during the Civil War, this veteran had been wounded and left for dead, and Brackett saved his life.

But Brackett persevered. In 1869, the U.S. Congress turned over to Storer three more buildings, along with the land they stood on. Black teachers and ministers joined the formerly all-white faculty. Frederick Douglass served as an early trustee.

Later History and Legacy

By 1872, the College had enabled 75% of Harpers Ferrry’s Black citizens to own real estate, an extraordinary number for the time (and a number that has yet to be matched today in most cities in the United States). An article in the school newspaper in 1892 declared, “When the time comes that the colored people of the South live in their own houses, cultivate their own farms, and read their own ballots, there will no longer be a race problem.”

Not until the twentieth century did the college live up to its name and to Storer’s condition. Throughout the remainder of the nineteenth century, it taught what we today would call elementary school, and later what was then known as “normal school” or teacher’s college. Finally, in the 1900s, Storer became accredited to grant two-year and then four-year degrees.

Storer held its students to strict behavioral standards. Students were required to have a Bible and attend chapel, Sunday School and daily assemblies. They were not permitted to attend dances on weekends, nor to leave the campus at all during the week. But the Storer community was also strong and nurturing. “Here you will gain new understanding of community living and of friendships,” said one grateful graduate. The school was also a center of the protest movement against Jim Crow laws in the early and mid twentieth century.

Nathan Brackett stayed on as principal until 1896 and remained on the board of trustees until his death in 1910. Even after Nathan’s death, members of the Brackett family served as trustees as long as the school was open.

And the End

But despite the dedication of the Brackett family, Storer closed its doors in 1955. It’s tempting to conclude that the West Virginia Board of Education closed the school out of malice, following the Brown v Board of Education decision in 1954. White malice was surely a factor, but the story is more complicated. Although the Freewill Baptists continued to fund the school and it also received a $20,000 annual stipend from the state, it continued to struggle financially. Average enrollment was only 176 students per year. Storer’s remote location in a declining industrial down wasn’t a draw. And, by 1955, Black students had many more options.

But Storer’s place in history was assured. For twenty-five years, it was the only school in West Virginia where a Black person could get any education beyond the elementary level. And over its eighty-eight years of existence, it educated over seven thousand future Black leaders.

Sources:

Most of the information in this post came from the excellent exhibits in the African-American History Museum of Harpers Ferry National Historical Park.

Other sources:

https://www.nps.gov/hafe/learn/historyculture/storer-college.htm