One of the bloodiest battles of the early twentieth century labor movement took place just a few miles from downtown Pittsburgh, in my old hometown of McKees Rocks.

Imagine earning only $122* for 110 hours of work over eleven days. You pay $400* a month to rent half of a small company-owned duplex. You have to buy all your groceries and supplies at inflated prices at a company store. On average, of the 6000 men working in your plant, one dies in an industrial accident every day. And your wife or daughter may be asked for sexual favors to help you keep your job or to forestall payment on your debt at the company store.

These conditions led to The Pressed Steel Car Strike in 1909. It was the most significant labor dispute in the Pittsburgh area since the 1892 Homestead Strike, and a precursor to the Great Steel Strike of 1919.

*Note: all dollar amounts in this post adjusted to 2022 dollars

The P&LE and the Pressed Steel Car Company

The Pittsburgh and Lake Erie Railroad started business in 1879, transporting coal, coke, iron ore, and limestone into Pittsburgh’s steel mills, and transporting the finished steel out. They located their 100-acre repair and maintenance center in McKees Rocks in 1888. The railroad employed thousands over the years, including one of my uncles. Immigrants flocked to the Rocks for the work opportunities. By 1920, the population of the town reached 14,702, 42% of which were immigrants. Between 1879 and 1920, many Italian and Slavic immigrants arrived, adding to the German and Irish populations already settled in the Rocks.

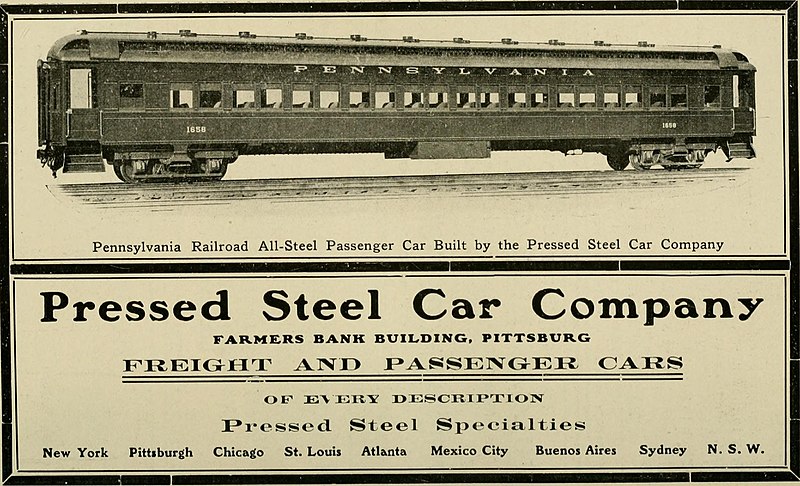

In 1899, in Joliet, IL, the Pressed Steel Co. and Fox Solid Press Steel Co merged to form The Pressed Steel Car Company. Run by Frank Norton Hoffstot, the company manufactured passenger and freight railroad cars.

At the time, it was the second-largest rail car producer in the United States. Locating a plant in McKees Rocks near the railroad hub and so much cheap labor seemed like a no-brainer.

Background of the Strike

By 1909, the plant employed 6000 men of sixteen different ethnicities, most of them foreign-born. But it had a reputation for brutal oppression. Workers called it “the last chance” and “the slaughterhouse.” The priest of St. Mary Roman Catholic Church in the Rocks said that “men are persecuted, robbed and slaughtered, and their wives are abused in a manner worse than death. . . all to obtain or retain positions that barely keep starvation from the door.”

Laborers worked under a “Baldwin contract,” a form of labor pooling. The company parceled out jobs in lots to foremen who contracted to get the work done for a set sum. The less the foremen paid the workers under them, the more they got to keep for themselves. So, the foremen had a strong incentive to race each other to the bottom of the pay scale. And workers couldn’t count on the size of their paychecks from one project to the next.

A newspaper reporter investigated the pooling scheme and found that one worker worked nine days, ten hours a day, and received pay of $89.53*. Before pooling, workers had averaged as much as $130* a day. But after pooling went into effect, average pay plummeted to $16* per day.

The strike begins

July 10, 1909, was a payday. Many workers noticed that their pay seemed especially scanty on that day, even less than the paltry amount they had bargained for. They demanded to speak to plant management. The managers refused. Violence erupted immediately. The first fatality was an immigrant worker named Stephen Horvat. More deaths would follow.

The leaders of the strike were a former German metalworker and union leader, Hungarian veterans of railway strikes, and three Russians who had been involved labor strife in St. Petersburg in 1905.

Five thousand of the plant’s 6000 workers joined the strike. Three thousand more from the Standard Steel Car Company of Butler also went out on strike in solidarity. The carpenters’ union sent wagons of food, and the Pittsburgh Leader newspaper took up a collection. Sensing an opportunity, the IWW (Industrial Workers of the World, sometimes called the “Wobblies”) came to the aid of the strikers. Big Bill Haywood himself, leader of the IWW, even showed up.

The company wasted no time in hiring scabs. By the end of July, 100 new workers had been brought into the plant, On July 14, a riverboat pulled up to deliver more strikebreakers. The strikers fired on the boat, forcing it to retreat. When deputy sheriffs tried to intervene, a riot broke out, resulting in 100 injuries from rocks, clubs and bullets. A mob of 1000 strikers attacked fifty mounted officers and broke a state trooper’s leg. Law enforcement got orders to shoot to kill.

Escalating Violence

On July 23, the company established an “information bureau” where workers could state their grievances. But the strike, and the violence, continued into August. In mid-August, the company hired 450 more strikebreakers. On August 19, strikers attacked streetcars bringing workers into the plant. On August 21, they shot at the company doctor, W. J. Davidson, as he approached the plant. Workers’ wives also joined the rioting. When state troopers and local deputy sheriffs arrived, the strikers attacked them, too.

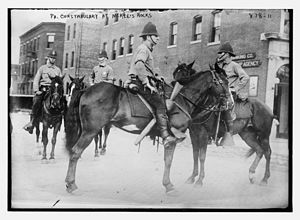

By August 22, 200 state constables (whom the Slav workers called “Black Cossacks”) and 300 deputy sheriffs had been deployed to protect the strikebreakers. That day, when strikers again boarded a street car to turn back scabs, armed deputies confronted them and opened fire.

The next day, the rioting strikers killed the deputy sheriff, Harry Exley. On August 22 and 23, the bloodiest days of the strike, Exley, two state troopers, and at least ten strikers lost their lives.

The Strike Ends

The tide of the strike turned on a newspaper photograph and an ill-advised attack on company housing.

The workers’ housing stood near the plant, in the little neighborhood called Presston (also known as Hunky Town). The area remained rural enough that workers had gardens to supplement their diets.

During the strike, the company began to evict workers, who were neither working in the plant nor paying their rent. On August 21, a local newspaper published a photograph of one family’s eviction. The photo included the heartbreaking feature of a baby buggy loaded into the wagon of possessions being carted away, and it gained much outraged sympathy for the workers.

Then, on August 23, state troopers stormed Presston to facilitate the evictions, attacking both men and women.

The Strike’s Legacy

The work stoppages and the bad publicity forced the company to settle the strike on September 8. The pooling practice ended. Wages were increased. The company began to offer English classes to immigrant workers. They improved housing in Presston, built a playground and planted trees. For many years after, the company sponsored free annual festivities on Independence Day, with races, garden competitions and cash prizes.

Workers won a victory on September 8, 1909, part of the labor movement’s long progress towards decent pay and working conditions.

The community of Presston still stands, in the form of about 200 duplex houses on Ohio and Orchard Streets.

The Pressed Steel Car Company went on to contribute significantly to the World War Two industrial effort, designing and produced tanks, gun carriages and motor carriers. The company was bought by U.S. Steel in 1956.

The P&LE Railroad went out of business in 1992.

The McKees Rocks Bottoms, where the P&LE yard and the Pressed Steel Car plant stood, is still home to a small railyard and several industrial plants, including Tudi Mechanical Systems, Standard Forged Products, and McKees Rocks Forgings. An historical marker and small memorial live on a nearby corner. The memorial is adorned with ten small American flags: one for each of the workers’ lives lost on August 22, 1909.

Sources

Agreen, Bernadette Sulzer, and the McKees Rocks Historical Society. Images of America: McKees Rocks and Stowe Township. Charleston, SC: Acadia Publishing, 2009.