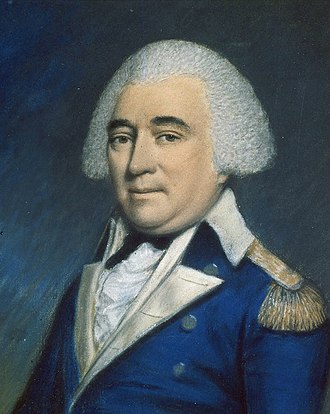

Was Mad Anthony Wayne truly mad? Not really. He just had a fiery temper. But legend has it that his ghost still haunts the state of Pennsylvania, where he was born, died, and became the father of the professional U.S. Army.

Wayne had pretty ordinary beginnings. Born in Paoli, PA, on January 1, 1745, he had only two years of education at an uncle’s academy in Philadelphia. In 1765, he worked for a year in Nova Scotia as a surveyor and agent for a land company. When the American Revolution broke out, he was working as a tanner and serving part-time in the Pennsylvania state legislature.

The American Revolution

In January of 1776, barely aged 21, Wayne assembled a militia and received an appointment as a colonel in the Fourth Pennsylvania Battalion of the Continental Army. He participated in the Army’s unsuccessful invasion of Canada later that year, successfully executing a rear-guard action at the Battle of Trois-Rivieres. Wayne also saw action at Fort Ticonderoga and Mount Independence. He protected Washington’s right flank in the Battle of Brandywine in 1777, and endured the brutal winter at Valley Forge. In the Battle of Monmouth, Wayne’s forces held out against a larger British force after General Charles Lee abandoned them.

Wayne’s finest hour as a commander was probably the Battle of Stony Point. He personally led a nighttime bayonet attack, and his columns stormed and captured the British fortification. Although the victory was more a morale boost than a strategic triumph, the Continental Congress awarded Wayne a medal for his courage and leadership.

Even after the British surrender at Yorktown, Wayne continued to serve his country. He helped disband the British alliance with Indian tribes in Georgia, and negotiated peace treaties with native tribes. After the war, he received a belated promotion to Major General and retired to a plantation in Georgia, seized from a loyalist and awarded to him for his service.

The Legion of the United States

This is the site of Legionville, near Baden, about a quarter mile from the Ohio River. Logstown, the Indian town that once stood here, burned in 1754. An Indian burial ground lies nearby.

In 1791, Washington called Wayne back into service. After Arthur St. Clair’s disastrous rout in Ohio, the President realized that he needed a general who could build a disciplined army, and Wayne had earned a reputation for both strict discipline and for seeing to the comfort and well-being of his troops. Wayne established a training camp at Legionville, near present day Baden and Ambridge, and spent the winter of 1791-2 turning a few thousand remnants of the Continental Army and some recruits from Pittsburgh into a formidable fighting force: the Legion of the United States.

Modern historians rightly point out that Wayne’s subsequent successful campaign in the West was one of many steps in the European genocide of the natives of North America. And that he owned slaves. As it happens, he was a less successful slavedriver than general. He went into debt buying enslaved people to work his Georgia plantation, and ended up bankrupt.

Weirdest Death Ever

Here’s Mad Anthony’s gravesite. Well, one of them . . .

But his death is the strangest part of Wayne’s colorful life story. Wayne’s rival for the position of General of the Legion, James Wilkinson, did not accept defeat gracefully. Wilkinson went out of his way to undermine Wayne and spread gossip about him. When Wayne received intelligence that Wilkinson was being paid as a spy for Spain, he began proceedings to court-martial him. But the court martial never happened. Wayne died on December 15, 1796. Some sources say he died of gout, others say a stomach ulcer. Rumors abounded at the time that Wilkinson had had him murdered. Wilkinson’s career as a spy wasn’t confirmed until 1854, almost forty years after his death.

But the story of Wayne’s death gets even weirder than that. After his death, Wayne was buried at Fort Presque Isle, near present-day Erie, PA. In 1809, his son, Isaac Wayne decided to disinter the body and move it nearer the family home in Wayne, PA. Imagine his surprise when he found the thirteen-year-old corpse in an astonishingly good state of preservation. A local doctor, James Wallace suggested boiling the body to separate the flesh from the bone, and then transporting the bones. Wayne’s flesh and clothing were reburied at Presque Isle, and the bones taken on the 400-mile journey to Wayne, PA.

Oh, wait, though, the weirdness isn’t even finished. When he arrived home, Isaac realized that he was missing some bones. They had apparently fallen out of the wagon along the way. So, Wayne is buried not in one grave, nor in two, but in a 400-mile trail of a grave.

Unsurprisingly, given the bizarre circumstances, legends abound that General Mad Anthony Wayne’s ghost haunts the state of Pennsylvania to this day, rising every New Year’s morning to ride the roads between St. David’s Episcopal Church in Wayne, PA, all the way to Erie, searching for his lost bones.

Coda

As I guess befits a man who is both a ghost and a war hero, and also has a problematic history as a perpetrator of both slavery and genocide, Wayne has several taverns named after him. There’s Mad Anthony Wayne Café, in Wayne, PA, General Wayne Inn in Merion, Pa, and Mad Anthony’s Taproom & Restaurant in Waynesville, NC. There are Mad Anthony Brewing Company locations in Fort Wayne, Auburn and Warsaw, IN. From 1950 until the 1990s, there was a Mad Anthony’s Bier Stube at 1233 Merchant St., in Ambridge, PA, a sniper’s bullet away from where he trained the Legion of the United States 230 years ago.

Sources:

https://www.nps.gov/vafo/learn/historyculture/wayne.htm

https://www.eriehistory.org/blog/a-halloween-story-the-death-of-anthony-wayne

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anthony_Wayne

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Wilkinson