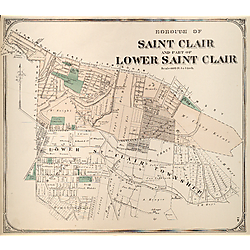

Continuing my series of posts inspired by our trip to Fort Ligonier this summer, I want to introduce my readers to Arthur Saint Clair. His name will sound familiar to those of us who live in the South Hills of Pittsburgh. He lent it to a vast township that once encompassed most of the southern suburbs and many City of Pittsburgh communities south of the Monongahela.

If you live in Baldwin Township, Knoxville, Mount Oliver, Mount Lebanon, or Upper Saint Clair, just to name a few, your community was once part of St. Clair Township. St. Clair Hospital in Mount Lebanon is named for Arthur Saint Clair, as are more than a dozen communities in Pennsylvanian and Ohio.

Once the largest landowner in western Pennsylvania, St. Clair died in poverty.

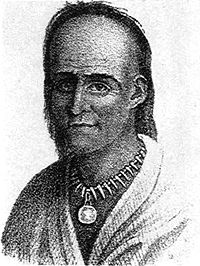

Student, Soldier, Landowner

He was born on March 23, 1736 in Thurso, Scotland. After attending the University of Edinburgh, St. Clair purchased a commission in the British army in 1757. He served in the French and Indian War, then resigned his commission in 1762. With assistance from his father-in-law, St. Clair purchased 4000 acres of western Pennsylvania land, making him the largest landholder west of the Appalachians. He settled in the Ligonier Valley with his wife, who eventually bore him seven children.

St. Clair joined the Continental Army in January of 1776 and was the Forrest Gump of the American Revolution, seeming to appear at nearly every important event. He was with Washington in the crossing of the Delaware and the Battle of Trenton. He commanded Fort Ticonderoga, was court-martialed for surrendering to the British siege, and found innocent. Back in Washington’s good graces, he was at Yorktown for Cornwallis’ surrender in 1780.

Governor of the Northwest Territory

As part of the Confederation Congress after the war, St. Clair helped to pass the Northwest Ordinance. Shortly after the passage of the bill, which created the Northwest Territory out of present-day Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan and parts of Minnesota and Wisconsin, Congress appointed him governor of the Territory.

As I live on land originally named for him, I’d like to say that he performed well. But, by our modern standards, St. Clair’s record in the Territory is troubling.

In the Treaty of Paris, which ended the American Revolution, Great Britain ceded to U.S. sovereignty all the land east of the Mississippi River and south of the Great Lakes. Slight problem: nobody had consulted the people who were currently living there. The weak American government sought to raise funds by selling plots of land in the Territory to white farmers. As St. Clair attempted to clear the Indians out of the Territory so the sale could proceed, they naturally resisted.

War With the Natives

In October 1790, St. Clair sent an army of 1500 men under General Josiah Harmar to destroy a major resistance village at the site of present-day Fort Wayne, Indiana. When that force was defeated, St. Clair decided to take matters into his own hands.

In September 1791, St. Clair led an expedition from Cincinnati towards Indiana. In the November 4 battle along the Wabash River, we can at least credit him with courage. Leading his troops himself, St. Clair had two horses shot out from under him and several bullets passed through his clothing. But, many of his militia had already deserted, and his army suffered a humiliating defeat. Of the 1400 men St. Clair had taken into battle, 623 were killed and 258 were wounded.

Not until 1794 would “Mad” Anthony Wayne win Ohio from its native inhabitants.

Washington ordered St. Clair to resign his commission in the Army, but he remained governor of the Northwest Territory until 1802. St. Clair worked to have the Ohio territory admitted to the Union as two states rather than one. He hoped this arrangement would preserve Federalist control of both states. New Democratic-Republican President Thomas Jefferson had other ideas, and relieved St. Clair of his position.

Death of Arthur Saint Clair

Upon his retirement from government, St. Clair returned to western Pennsylvania. Congress never reimbursed him for his expenses from his time as Northwest Territory governor. St. Clair lent generously to family and friends, and made some loans that were also never repaid. By the early nineteenth century, he had lost his fortune and most of his vast land holdings. He died in a small log cabin near Greensburg on August 31, 1818, at age 81. He is buried under a Masonic monument in downtown Greensburg.

The parlor of St.Clair’s home in Ligonier is beautifully recreated at the Fort Ligonier Museum.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arthur_St._Clair

https://historicpittsburgh.org/islandora/search/catch_all_fields_mt%3A%28lower%20saint%20clair%29

https://ohiohistorycentral.org/w/Arthur_St._Clair

https://www.pittsburghbeautiful.com/2018/02/20/pittsburgh-suburbs-history-of-upper-st-clair/