When she was in her 20s, Dorothy Day would have seemed like a long-shot for sainthood. She lived a bohemian lifestyle including multiple lovers, an abortion and a child born outside of marriage – and this was in the 1920s, when society didn’t exactly shrug at that as we do today. She was, at various times, either an Anarchist or a Socialist.

When she was in her 20s, Dorothy Day would have seemed like a long-shot for sainthood. She lived a bohemian lifestyle including multiple lovers, an abortion and a child born outside of marriage – and this was in the 1920s, when society didn’t exactly shrug at that as we do today. She was, at various times, either an Anarchist or a Socialist.

But…raised in a non-church-going family, Dorothy had had an interest in religion as a child, and her spirituality was re-awakened with the birth of her own child. And her sense of social injustice had been kindled by her encounters with the poor and working class during her years as a pacifist, Socialist and suffragette.

As she approached 30, Dorothy became very attracted to Catholicism and received baptism in 1927. Never one to do anything by half measures, she took very seriously Christ’s injunction to feed the hungry, clothe the naked and care for the sick and the stranger.

With Peter Maurin, she co-founded the Catholic Worker newspaper in 1933. The Catholic Worker advocated for the poor and the working class. Day and Maurin argued against both big business and big government, and tried to present an alternative economic vision that in many ways harkened back to early-19th century America: small farms, small businesses, widespread property ownership, and a reliance on the individual, the family and the community.

Day and Maurin advocated for the lower classes in their deeds as well as their words. They embraced “holy poverty” in their own lives. They refused to accept advertising in The Catholic Worker and the newspaper’s staff was unpaid. Most of the proceeds from the Worker (which had a peak circulation of 190,000 in 1938) funded Hospitality Houses in the Lower East Side of Manhattan, which provided food and clothing to the poor of the community. They also founded Catholic Worker farms, where the sick and homeless could recover and the idle could find useful work.

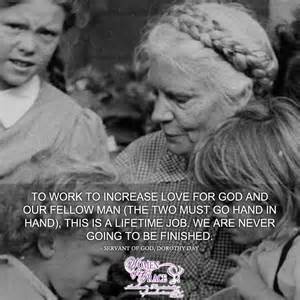

The Worker’s extreme pacifism was unpopular during World War Two, and the newspaper’s circulation declined significantly. Peter Maurin died in 1949. But the Catholic Worker movement lived on. Over 200 Catholic Worker communities still operate today, in cities and on farms. Dorothy Day continued her life of writing, activism and holy poverty until her death in 1980. She was first proposed for sainthood in 1983. In March 2000, Pope John Paul II approved the case to go forward, which allows her the title “Servant of God”. The formal application for sainthood was received by the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops in 2012 and is still pending.

What I admire most about Dorothy Day is her total fidelity to Christ’s words in Matthew 25:40: “Just as you did it to one of the least of these who are members of my family, you did it to me.”

What I find most intriguing about her is her opposition to both big business and big government, her ultimate rejection of Socialism as well as her rejection of rampant crony capitalism. Did Dorothy and Peter imagine some middle way that could be unifying for our Divided States of America in the 21st century? I plan to do some more reading on this topic, and I will report on it in future blog posts.