Category Archives: Blog

On Faith and Doubt

I wrote last week about my faith. This week I want to cover the concept of doubt, and explore why, for me, they are not necessarily opposites or even incompatible.

I wrote last week about my faith. This week I want to cover the concept of doubt, and explore why, for me, they are not necessarily opposites or even incompatible.

I remember the moment when I first doubted. I was in college, sitting in the back yard of my apartment building. I was reading something, probably for school, but I don’t remember whether it had anything at all to do with religion or philosophy. What I do remember is that the thought suddenly came into my head, in these exact words: “There might not really be a God.” I was 21 years old, and this had never occurred to me before. I was stunned. I felt a vast emptiness that was terrifying and exhilarating at the same time.

Once you know something, you cannot un-know it. I have lived with that doubt every single day of my life since.

For a while, I felt proud and defiant. I stopped going to church and I and argued with believers (“But how do you know? You can’t know. There’s no proof.”). Then I went through a period of envying other people their certainty, wishing I still had mine.

But, over the years, I’ve learned to let my love of Christ live comfortably in the same house with my doubts as to whether there is any God at all. It’s not that I don’t think it matters whether or not the Christian story is objectively true. It matters very much. If it’s true, it changes absolutely everything. I just don’t expect to ever know whether or not it is objectively true, at least not in this life.

It may be that certainty is a form of Grace that is given to some and not to others. It may also be that doubt is a form of Grace that is given to some and not to others. A person who doubts is thinking about faith, not taking it for granted. Concepts like “God” and “Salvation” seem to me to be too mysterious, too enormous for the human mind to comprehend in a lifetime. They warrant constant questioning and contemplation.

Jesus said, “Blessed are those who have not seen and yet have believed.” People who are absolutely certain about the objective truth of their faith’s stories are those who have “seen.” Those of us who believe without that certainty of having “seen” are, I think, blessed in a whole different way. We cannot take any pride in our own tiny faithfulness, so we must stand before the Cross and humbly rely on Christ’s unlimited faithfulness to us. We dwell in awe and mystery, always – in Rilke’s words – “living the questions.”

Note: the graphic included in this post is the Pillars of God nebula, an image that often comes to mind for me when I contemplate God’s unfathomable power and glory.

Why I Am Still a Christian

I believe in God because the universe leaves the door ajar. Even in this marvelous century, when science can tell us how to get to Mars, and what percentage of our DNA is shared with howler monkeys, and exactly which mutated gene most likely caused my breast cancer, science still can’t tell us why: why there is something and not nothing, why each of us is uniquely who we are, why we hold in our hearts notions like justice and mercy in a world where both are tragically rare. So the door is left open just a crack for art and philosophy and religion to rush through.

I believe in God because the universe leaves the door ajar. Even in this marvelous century, when science can tell us how to get to Mars, and what percentage of our DNA is shared with howler monkeys, and exactly which mutated gene most likely caused my breast cancer, science still can’t tell us why: why there is something and not nothing, why each of us is uniquely who we are, why we hold in our hearts notions like justice and mercy in a world where both are tragically rare. So the door is left open just a crack for art and philosophy and religion to rush through.

But that doesn’t demonstrate anything about the truth of the Christian story in particular. There are some good arguments for the plausibility of Christianity. Something incredible must have happened to inspire so many of Christ’s early followers to submit to martyrdom. And the Church, by fair means and foul, has stood the test of time. But the fact remains that no religion can be proven to be true. This is why such beliefs fall under the heading of faith rather than science. They can’t be logically or scientifically demonstrated. We believe our faith stories for other reasons.

Jesus was presented to me as God by people I loved and who lived his message in their daily lives. My mother’s family were Catholics and faith was central to their lives. My grandparents never missed weekly Confession and Mass. They had a small font of holy water by their front door, regularly refilled by a parish priest, which we used to bless ourselves when entering or leaving the house. Three of my mother’s cousins were nuns, a source of great pride to our family, and the cause of many family outings to convents on family visiting days. But, my people were not simply pious; they lived their Christian faith. My grandmother sewed First Holy Communion dresses and veils for poor little girls whose families couldn’t afford a lovely outfit for that big occasion. Her sister was a social justice and Civil Rights activist, a lettuce boycotter and a deliverer of packages of food, clothing and books to families in the poorest section of our city. My most vivid memories of my grandfather are of him sitting in his special chair in the dining room, praying and reading his devotions. As a young man, he and his friends had raised money and said special prayers to the Child of Prague for the healing of a friend’s seriously ill child. For the rest of his life, he had special devotion to the Child of Prague, and often gazed upon the small icon of the Child in his dining room. He was doing exactly that when he died quietly at the age of 91, with 3 of his 4 children in the next room.

My father’s people were Lutheran, and it was to the Lutheran church that I was taken as a child. It was a tiny church in a working-class neighborhood where everyone knew everyone else, and took care of each other. Several of my father’s aunts and uncles belonged to this little church, and I was treated with great gentleness and love by these kindly, humble people. My father’s faith was at the center of his life when he was a young man, before alcoholism claimed him. He sang in the choir, and served multiple terms as president of his church council. Like my grandparents, he lived Biblical command to be especially kind to the humblest people. There was an overweight, unattractive, rather tedious elderly woman who attended our church. She didn’t drive and her abusive husband refused to give her a ride to church. My father picked her up for church every single Sunday for years. When he dropped her off at home, he always got out of the car with her and walked her up to her door. “Watch your step, Frances,” he said every single week, gently and patiently supporting her by the elbow.

These were the examples I had of how to be human in an imperfect world, of what it meant to behave as a follower of Jesus Christ. My love of Christ is inseparable from the very notion of love itself because of these early lessons.

Now that I’ve made all my atheist and agnostic friends roll their eyes, I will continue by disappointing my Christian friends next week with a blog post about why I still live with doubt every single day.

Augustine of Hippo died on this date in 430

Saint Augustine’s death was indirectly at the hands of a heretic Christian.

Saint Augustine’s death was indirectly at the hands of a heretic Christian.

The city of Hippo Regius was 1000 years old by the time Augustine became its bishop. It was the second largest port in North Africa, after Carthage. The main part of the city was built on two hillocks, where the mouth of the Seyhouse River formed a good harbor. Most of Augustine’s parishioners would have been farmers on the river plain, growing grapes, olives and grains. North Africa in Augustine’s time, less dry than it is today, was the breadbasket of the Roman Empire.

Augustine’s time as bishop was far from strife-free right from the start. The Church in North Africa was still fighting the Donatist heresy, and the city’s suburbs were threatened from time to time by semi-nomadic tribes from the south.

But the gravest, and final, threat first made itself known in 428. The Vandals originated in Eastern Europe, but were settled in Spain by the early 5th century. In 428, for obscure reasons, their king Genseric took his army of 80,000 across the strait of Gibralter. By the standards of the time, they swept rapidly eastward across North Africa, overrunning the colonies of Mauretania and Numidia. The Roman armies simply collapsed and retreated before them. Bishops and citizens fled their towns. Churches were set on fire. Captives were tortured, and women suffered the usual fate of women in wartime. By the winter of 430, the Vandals reached Hippo. By May, they had surrounded the city and their fleet blocked the port.

The interesting thing about Genseric and his horde is that they were Christian.

Genseric was an Arian, another of the many early Christian heresies with origins in dogmatic, disputatious North Africa. The Arian heresy was simply that the Son and the Father were not co-eternal, that God the Father created his Son Jesus at a point in time. This ran completely counter to the Trinitarianism that was becoming orthodoxy in the early Church. Augustine grieved over the suffering of his Hippo flock, but by all accounts he never even considered surrender. Anyone who survived a Vandal attack was converted at sword-point, and Augustine believed his parishioners would be better off dead than converted to heresy.

In his own case, the choice was taken out of his hands. Saint Augustine died a few months into the siege, on August 28, 430. He was 75. The cause of death is usually described as “a fever,” probably brought on or compounded by stress and starvation.

The siege itself continued for a total of 14 months. Interestingly, sources disagree as to whether the city finally surrendered or whether Genseric simply abandoned the project and moved on.

The Summer We Were Poor

The summer before I started ninth grade was the summer when my family was poor. We were poor in a new 3-bedroom ranch house in a tidy little development, so we had to be secretly poor, but we were poor nonetheless. My father had finally drunk himself out of a job and now spent his days drinking Fort Pitt beer in front of TV soap operas, disintegrating in front of our eyes, 40 years old and already gaunt with hairless legs and a patchy scalp. My mother took a job. She was 35, weighed less than 100 pounds, looked younger than I did, and must have seemed out of place in front of her IBM Selectric, a tiny pre-adolescent supporting a family of five.

The summer before I started ninth grade was the summer when my family was poor. We were poor in a new 3-bedroom ranch house in a tidy little development, so we had to be secretly poor, but we were poor nonetheless. My father had finally drunk himself out of a job and now spent his days drinking Fort Pitt beer in front of TV soap operas, disintegrating in front of our eyes, 40 years old and already gaunt with hairless legs and a patchy scalp. My mother took a job. She was 35, weighed less than 100 pounds, looked younger than I did, and must have seemed out of place in front of her IBM Selectric, a tiny pre-adolescent supporting a family of five.

Our radio broke and we didn’t buy a new one. Our ’65 Chevy Bel Air was tempermental. Some mornings, my mother drove to work, other mornings, when the Chevy was in a bad mood, she walked, or called someone for a ride. Towards the end of a pay period, lunch was whatever I could find in the kitchen: graham crackers and dill pickles, chicken noodle soup and powdered milk, saltines with jelly. My younger brother and sister were often invited to lunch at friends’ houses. Dad pretty much stuck with his pal, Fort Pitt.

Patti Ann next door, who had recently graduated from high school and gotten a secretarial job downtown, gave me 2-year-old copies of Glamour and Seventeen, and her cast-off clothing. I pored over the magazines, wishing that I knew boys on whom I could practice “The Art of Flirting” or “How to Get Asked on a Second Date.” I studied the fashions, and ripped apart my own old clothes and Patti Ann’s cast-offs and made myself new clothes: a halter top from the top of a baby-doll dress, shorts from too-short bell-bottoms, a belt from the strap of a handbag.

I spent as much time as I could away from home. Instead of watching the soaps with my father, I watched them at my friend Judy’s house. Judy’s parents were elderly, retired, grim-faced people. They were careful with money and never invited me to stay for a meal, but their house was air-conditioned and Fort-Pitt-free, and Judy’s mother watched the soaps without making alcohol-fueled comments about what she thought the characters would do next.

I had just the right combination of curiosity, worldliness, naivte and luck to get into trouble, but not big trouble. I rode the bus to Oakland and necked on a bench with a college boy that I met just that day on the University of Pittsburgh lawn. I lied and told my parents I had a ride to a dance, and then walked the 3 miles there at 7:00 and the 3 miles home at almost midnight. On my way home, a man exposed himself to me in between two houses. His hairless naked body shone white in the moonlight. I stood in shock for just a split second, like a cartoon character with exclamation points radiating from my head, and then I ran, my coltish 13-year-old legs pumping, wooshing through the summer night air, not stopping until I reached the first busy, well-lit street. I ran right into a girl I knew, older than me, the kind of girl who smoked cigarettes, wore dark eyeliner and made up mean nicknames for sensitive, studious girls like me. In a shaking voice, I told her what I had just seen. Telling a tough girl like Debbie made me feel brave and mature, as if she and I now shared some level of sophistication and dark worldliness. Debbie listened and smoked, and didn’t offer me a cigarette. She squinted through her exhaled smoke and approved of my “getting the hell out of there.” She told me that her boyfriend wanted to have sex with her and that she would never consent to this, even if he got down on his knees and kissed her “rosy red ass.” I felt a sudden, passionate loyalty to her that wouldn’t let me admit to myself that I suspected that she probably would have sex with him, and soon. We were two very different girls who barely knew each other, walking together late on a summer night, sharing secrets. She was the only person I ever told about the flasher, but the next time we saw each other, we didn’t even say hi.

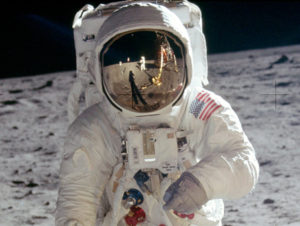

It was the summer of Woodstock, one of nine summers of the Viet Nam war, the summer of the moon landing. I watched Neil Armstrong’s historic steps on my grandparents’ black-and-white TV. The picture was grainy and blurry, Armstrong’s voice staticky. Afterward, my uncle and I went out on the porch and looked up at the moon, a skinny 13-year old and a balding 37-year-old bachelor grad student. Neither of us said anything. We just sat on the porch together for a long time and looked at the moon and thought about people being there for the first time.

My family was poor. I was a skinny, studious girl, neglected by distracted parents and isolated for the summer from most of my school friends. With no radio, I missed all the hit songs of the summer: Hair, Get Back, Grazin’ in the Grass. I never heard the song McArthur Park until 1972. I borrowed books from the library and read lying in front of the fan if my father wasn’t in the living room, and holed up in my hot, stuffy bedroom if he was. I made my own clothes from whatever was at hand. And I daydreamed about a better life, a life that was no less possible, after all, than putting a man on the moon.

Augustine and his world (part two)

One of the things that most fascinated me about Augustine and his mistress, and made me want to write about them, was the time in which they lived. It was a turning point: the end of the Roman Empire and the start of what we call the Dark Ages, the time when the Ancient World collapsed and the Christian Era began.

The Christian church was still deciding what orthodoxy would consist of. Heresies abounded: Pelagianism, Arianism, Appolonianism, the Donatist heresy that forms much of the backdrop for Part One of The Saint’s Mistress.

Non-Christian influences on early Christian thought, and on Saint Augustine in particular, included Stoicism, Platonism and especially neo-Platonism – and, of course, Manicheism. Augustine had an excellent education in what we now call the classics. He would have read books that are now lost to us, such as Cicero’s Hortensius, which taught that happiness comes from studying philosophy.

Neo-Platonism was ascendant among the Milan intelligentsia during Augustine’s time there. By the time he arrived in Milan in 384, Trinitarian Christianity was established as the official state religion, but the court intellectuals tried to steer a skeptical course between Christianity and pagan philosophy. These men (of course, they were almost all men) were not so different from many modern thinkers. They liked feeling like they had control over their lives. They had a hard time with the surrender required of Christians, the notion that we are redeemed only by Christ’s blood, not by our own acts. Even long after he repudiated the Manichees, Augustine himself clung very hard for a while to the notion that man could somehow “ascend” through study and philosophy.

It was also a time of great turmoil. During Augustine’s time in Milan, legions were usually posted both inside and outside the city walls, to defend against the Barbarian invaders who regularly crossed the Alps from present-day Germany, seeking plunder. The Empire was crumbling, and that became clearer over the course of Augustine’s long life. The legions were progressively withdrawn from the further reaches, such as the border area between the North African provinces of the Empire and tribal central Africa.

Taxes were high and growing higher. The class divide was wide and growing wider. The rich had indoor plumbing, central heating, walls and flooring or rich mosaic tile, and multiple slaves. The growing class of urban poor slept in the porticos surrounding the outer courtyards of churches. Crime was on the increase, as small farmers were forced off their land by large landowners, and slaves put the lower classes out of work. Punishment was severe for lower-class people convicted of crimes: they could be buried alive, thrown from a cliff scourged, or sent to the mines or the arena.

In 387, Augustine, Adoedonatus and Monica were delayed in Ostia because the sea lanes were blocked by a war between the eastern & western Roman Empire, sparked the by usurper Maximus. It was during this delay, waiting to embark for a return to North Africa, that Monica died.

And, of course, Augustine’s life ended during the siege of Hippo Regius, led by the Visgoth Alaric, an Arian heretic who had already sacked Rome and present-day Spain, then crossed the Gibralter Strait to bring war, plague & pestilence to North Africa.

In my book, I portray Aurelius Augustine and his fellow intellectuals living in the midst of this turmoil and understanding that the classical world order was ending. The power and importance of the Christian church was on the rise. Quintus sees the Church as his ticket to power and comfort. Others turn to the Church as a comforter and protector in a tumultuous time. These are practical and understandable reactions and don’t necessarily exclude the possible truth of the Christian message. God can work in mysterious ways his wonders to perform. But, I felt that my main characters had to be morally an intellectually convinced. Leona is an honest woman, and Aurelius Augustine is a passionate seeker of truth. I didn’t think it would honor them to have them become Christians for any reason other than that they were convinced of its truth.

Virtual tour of early-Christian-era Rome

Rome a few decades before Augustine’s time. Note especially the the vast size of both the aqueduct and the Circus Maximus! Other large cities where Augustine lived – Milan, Carthage – would have looked similar. Just as Western architecture and urban design are predominant in the world today, the rest of the Empire followed Rome in the early Christian era. 320, of course, is only 7 years after the Edict of Milan legalized Christianity. One big difference between this landscape and the landscape of Augustine’s time would have been an increase in the number of Christian churches.

Gandalf quotes Augustine

I found a quote from Saint Augustine that I’d never heard before….and it reminded me of what Gandalf says to Frodo in The Lord of the Rings. Tolkein was a well-educated Christian, and I doubt that he placed these words in Gandalf’s mouth by accident.

Augustine’s words:

Gandalf’s words:

President Obama explains why I write

I just finished reading a wonderful article in the April issue of The Atlantic, which described a meeting that President Obama had with Marilynne Robinson. This absolutely enchants me. I’ve always been an Obama supporter, but now I’m seriously in love with him. First, Robinson is one of my favorite writers. Second: The PRESIDENT met with a NOVELIST because…well, I can’t state it any better than he did: “When I think about how I understand my role as a citizen, setting aside being president, and the most important set of understandings that I bring to that position of citizen, the most important stuff I’ve learned I think I’ve learned from novels. It has to do with empathy. It has to do with being comfortable with the notion that the world is complicated and full of grays, but there’s still truth there to be found, and that you have to strive for that and work for that. And the notion that it’s possible to connect with someone else even though they’re very different from you.” That’s why I read, that’s why I write, and that’s why I am now the President’s most starry-eyed and abject fan-girl.

I just finished reading a wonderful article in the April issue of The Atlantic, which described a meeting that President Obama had with Marilynne Robinson. This absolutely enchants me. I’ve always been an Obama supporter, but now I’m seriously in love with him. First, Robinson is one of my favorite writers. Second: The PRESIDENT met with a NOVELIST because…well, I can’t state it any better than he did: “When I think about how I understand my role as a citizen, setting aside being president, and the most important set of understandings that I bring to that position of citizen, the most important stuff I’ve learned I think I’ve learned from novels. It has to do with empathy. It has to do with being comfortable with the notion that the world is complicated and full of grays, but there’s still truth there to be found, and that you have to strive for that and work for that. And the notion that it’s possible to connect with someone else even though they’re very different from you.” That’s why I read, that’s why I write, and that’s why I am now the President’s most starry-eyed and abject fan-girl.

Augustine and Manicheism

Here’s a brief article that summarizes Manicheism and Augustine’s original attraction to the sect.