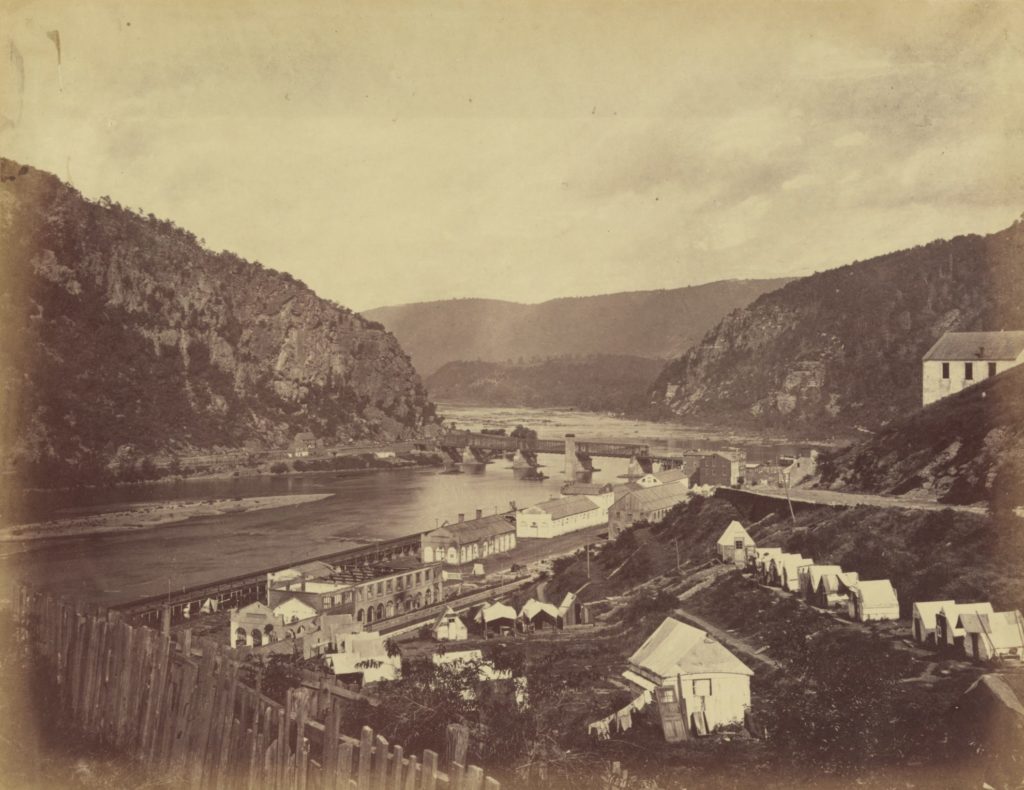

Tall, craggy cliffs tower over the confluence of the Potomac and Shenandoah Rivers, topped by frost-covered trees like gray ghosts. On the bright winter day when we visited Harpers Ferry, the Potomac stretched broad and green below us, dotted with frost-glazed rocks, while the busier, bluer Shenandoah rushed to meet it.

The majestic beauty of the scene seemed just the right stage for the dramatic events that occurred there in 1859

Harpers Ferry Early History

The first known settlers in the area that would later be named Harpers Ferry were Patawomeck Indians who called their village Pomeiock.

But, with the coming of the white man, it didn’t take Europeans long to recognize the advantages of the spot where present-day Maryland, West Virginia and Virginia meet. In the eighteenth century, the land officially belonged to Lord Fairfax. But the first white settler was Peter Stephens, in 1732. In 1747, Stephens sold his squatters rights to Robert Harper for 30 guineas. Harper got a patent on 125 acres around 1750 and by 1761 had established the ferry service that would give the town its name. Harpers Ferry became a starting point for settlers moving into the Shenandoah Valley and further west.

Ferry service ended in 1824, with the construction of a covered wooden bridge. But by then, Harpers Ferry already bustled with industry. The town’s history as an industrial town began when George Washington proposed the site for an armory and arsenal. Construction began in 1799, and the arsenal eventually produced more than 600,000 muskets, rifles and pistols between 1801 and 1861. It supplied the tomahawks, knives, guns and other equipment for the Lewis & Clark expedition in 1803.

At its peak, the town at one time boasted 3000 residents and multiple busy factories in addition to the arsenal, powered by the rushing waters of two rivers: a bottling plant, a pulp mill, a cotton factory, machine shops, a flour mill, a cooper, blacksmith, iron foundry, sawmill, chopping mill and wagon maker.

Harpers Ferry was the home of the first successful use of interchangeable parts. John Hall of Hall’s Rifle Works pioneered the notion of using the same parts in multiple products, a technique that was as important to the industrial revolution as Henry Ford’s assembly line.

But today Harpers Ferry’s fame rests on only one thing – and one man.

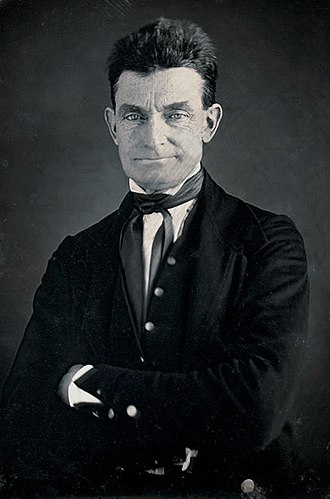

John Brown

John Brown was born in 1800 in Torrington, Connecticut. Married twice, he fathered twenty children. He moved around a lot, living at various times in Ohio, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, New York and Kansas. He succeeded and then ultimately failed at several different businesses, including leather tanning, surveying, raising livestock, sheep farming and real estate.

A passionate abolitionist, Brown was a conductor on the Underground Railroad, and formed the League of Gileadites to help runaway slaves escape to Canada.

In 1855, he moved to Kansas. Kansas in the 1850s was a battlefield between pro- and anti-slavery advocates. And I mean the word “battlefield” literally. In response to the sacking of Lawrence, KS, by a pro-slavery gang, Brown led a small band to Pottawatomie Creek on May 24, 1856. They dragged five unarmed men and boys – whom they believed to be pro-slavers – from their homes and brutally murdered them. Then they rode into Missouri, freeing eleven slaves and murdering their owner.

It seems incredible today that Brown never faced any justice for these murders. Instead, he spent the next two and a half years traveling through New England to raise money for anti-slavery activity in the South.

By 1859, Brown had come up with a plan to spark a slave rebellion in Virginia. He and a group of about two dozen followers, including four of his sons, rented a farmhouse four miles north of Harpers Ferry. To deflect suspicion, the men took women with them, including Brown’s daughter Annie and daughter-in-law Martha, and rented the farmhouse under the alias Isaac Smith. The men trained for an operation that would capture the arsenal at Harpers Ferry and arm Blacks to rebel against their enslavers

Somehow, the plan leaked. Brown heard that a search warrant was imminent, so he decided to launch the attack eight days earlier than planned.

Brown Attacks

At 11 p.m. on October 16, Brown left the women and three men at the farmhouse as a rear guard, and led the rest of his band across the bridge into Harpers Ferry. They took as their first hostage Lewis Washington, great-nephew of George Washington, freeing his twelve slaves and seizing two valuable Washington relics.

They then cut the telegraph lines in both directions. A free Black B&O Railroad baggage handler, Heyward Shephard, was killed when he accidentally encountered the raiders.

Taking the armory was the easy part. In the middle of the night, only one man guarded the armory, and he handed over the keys. As soon as other armory employees arrived for work early in the morning, they were taken hostage.

Executing the rest of the plan was harder. Brown assumed that his gang would only have to hold the arsenal on their own for a few hours. He’d assumed that slaves would rally to his cause as soon as they heard about it, and, once armed, would march through the area freeing more slaves. But he apparently hadn’t thought through how to get the word out to the enslaved. Soon enough, though, word got out to those less friendly to his cause.

The Raid Begins to Falter

Brown controlled the rail line, but allowed a train passing through town to go on to the next stop in Monocacy, where the conductor alerted government & railroad executives to the raid. By noon, several companies of militia had arrived, taken the bridges and cut off Brown’s escape.

Brown and his men retreated to the arsenal’s small fire engine house, known today as John Brown’s Fort. The militia were poorly armed and many of them were drunk by afternoon. The militia combined with angry townspeople to form an angry, drunken, ineffective mob. The battle for the arsenal became a standoff.

President Buchanan then called in the Marines from Washington Navy Yard, only about sixty miles away. The Marines’ commander, Colonel Robert E. Lee, hastily arrived from his home in Arlington in civilian clothes. But he also had with him 81 privates, 11 sergeants, 13 corporals, a bugler, and seven howitzers.

Lee sent J. E. B. Stuart to offer Brown’s party surrender terms. Brown was having none of it. And so the attack commenced. Lee’s forces fairly quickly broke down the doors of the engine house. After that, the battle took all of three minutes.

Ten of Brown’s raiders were killed, including two of his own sons. Brown and three others were captured. Seven of the raiders escaped, but two of those were also later captured. One of the escaped and later captured was Brown’s son Owen. The Marines had to protect the captured raiders from the drunken mob outside the arsenal.

All of the hostages were freed. Eight militia were wounded. Lee’s forces suffered only one casualty.

Aftermath of the Raid on Harpers Ferry

On November 2, 1859, John Brown was convicted of treason against the Commonwealth of Virginia and inciting a slave insurrection. On December 2, he was executed by hanging. In one of those you-couldn’t-make-this-up coincidences, witnesses at his execution included Walt Whitman and John Wilkes Booth. At his trial, John Brown said, “…if it is deemed necessary that I should forfeit my life for the furtherance of the ends of justice, and mingle my blood further with the blood of my children and with the blood of millions in this slave country whose rights are disregarded by wicked, cruel, and unjust enactments–I submit; so let it be done!”

An already divided nation quickly took sides on the matter of the raid. To many in the North, Brown was a martyr. The South was infuriated. Ardent pro-slavery activist Edmund Ruffin, among others, claimed that the raid proved that the North actively supported slave rebellion. Distrust between the two factions grew. A catastrophic Civil War soon followed.

As for the town of Harpers Ferry, it never recovered. The day after Virginia seceded from the Union, the U.S. Army emptied the armory and burned the arsenal. The town changed hands eight times during the Civil War and was also subject to multiple floods in the decades that followed, and industry declined. From a high of 3000 in the nineteenth century, the population of Harpers Ferry has fallen to about 250 people, with the National Park its main attraction – along with, of course, the mighty cliffs and beautiful rivers that will stand long after all warring nations have passed away.

A Thoroughly Enjoyable Day

Al and I thoroughly enjoyed our visit to Harpers Ferry National Park. It was off-season, but most of the exhibits were open, and we had them mostly to ourselves. I have never been disappointed in any of our National Parks, and this one was no exception. The exhibits were very well done, thought-provoking and informative. Sadly, we lost most of our photos due to a glitch with Al’s camera that we still haven’t figured out, so the photos in this post are mostly grabbed from the internet.

One our way home, we had a very good lunch at Tom’s Taphouse in the pretty little town of Boonsboro, Maryland. Boonsboro was founded in 1792 and still features at least three log structures still in use. One is a pottery, one is a tattoo parlor, and the other is a private residence.

Watch for my next post later this month. I’ll write about some interesting African-American history that we discovered in Harpers Ferry, and the final verdict (in my opinion) on John Brown.

Sources

Most of the information in this post comes from the excellent educational exhibits at Harpers Ferry National Park.

Other Sources:

http://harpersferrywv.us/about.htm

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harpers_Ferry,_West_Virginia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Brown%27s_raid_on_Harpers_Ferry