Some of us who live in Pittsburgh and Philadelphia jokingly call the rest of our state “Pennsylbama,” referring to the rural nature of northern and central Pennsylvania and to the anti-government, anti-tax political sentiments of the area’s residents. But most of us aren’t aware that the roots of those sentiments go all the way back to the first major challenge to the sovereignty of the young United States. That challenge was the Whiskey Rebellion, and it took place right here in southwestern Pennsylvania.

Hamilton – AGAIN

Anyone who’s seen the musical “Hamilton” or read the excellent Ron Chernow biography on which it is based, knows that the first Secretary of the Treasury advocated federalizing the finances of the young nation. He fought for a national bank. He wanted the federal government to take over state debts resulting from the Revolution. But how to raise the revenue to pay off that debt?

Hamilton proposed a tax on whiskey, and Congress enacted it in 1791. You can see why they thought it would be a good idea. They believed that the tax would fall on a small minority of citizens. And sin taxes are common sources of revenue. Since sin is pretty consistent, they also tend to be very reliable sources of revenue.

What Hamilton failed to consider was that, on the western frontier, fully one man in five was running a whiskey still.

“Look, when Britain taxed our tea, we got frisky; Imagine what gon’ happen when you try to tax our whiskey”

The reaction to the tax was intense. Western Pennsylvania was the frontier in 1791, a virtual wilderness. It was expensive for area farmers to transport their grain to the east for sale. But whiskey was both easier to transport and more profitable. The rye that they grew sold for 40 cents a bushel. A packhorse could carry four bushels east, earning the farmer on $1.60. But the same pack horse could carry twelve bushels if they had been turned into eight gallons of whiskey – which sold for $1 a gallon. Eight dollars versus $1.60. Even 18th-century farmers could do math.

Also, currency was in short supply on the western frontier. Deer hides and whiskey were used for barter just like cash. One farmer put it this way: He never saw more than $10 cash in a year, spent mostly on “salt, nails and the like; nothing to wear, eat or drink was purchased, as my farm provided all.” So, to many small farmers in southwestern Pennsylvania, the whiskey tax amounted to an illegal income tax.

Perhaps worst of all, the tax seemed intended to favor large distillers over small ones. The sales of large distillers were easier to measure, so they were taxed on what they actually sold. The little guys were taxed on the size of their stills, which may or may not correspond to what they actually produced and sold. Small distillers who couldn’t afford to post a tax bond also had to pay their tax up front, and they had a harder time passing the cost of the tax on to customers.

The Whiskey Rebellion begins

The tax act passed in the U.S. Congress on March 3, 1791. It took a while for the news to make its way west and for the guys with stills in their backyards to reach the conclusion that Secretary Hamilton was trying to put them out of business in favor of rich, smart guys like himself. Angry small distillers from all four southwestern counties – Allegheny, Fayette, Washington and Westmoreland – met on July 27, 1791 at an old French & Indian War fort in Connellsville. They agreed that rebel groups would be formed in each county, meeting in the county seat to plan resistance measures.

The Allegheny County rebels met for a three-day brainstorming session at the Whale and the Monkey Tavern (later renamed the Sign of the Green Tree) in Pittsburgh, between September 6 and 8, 1791. The tax rebels signed a formal petition that went both to the U.S. Congress and the Pennsylvania state legislature.

Their petition was actually successful. . .sort of. Congress reduced the tax by one cent.

Let’s just say that the westerners were less than satisfied.

Tar, Feathers and Haircuts

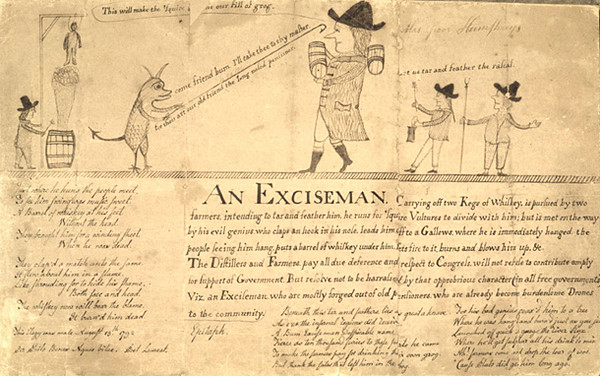

The rebels issued a decree that said, in part, that any person “who had accepted or might accept an Office under Congress in order to carry (the tax) into effect, should be considered as inimical to the interests of the Country; and recommending to the Citizens of Washington County to treat every person who had accepted or might thereafter accept any such office with contempt, and absolutely to refuse all kind of communication or intercourse with the Officers, and to withhold from them all aid, support or Comfort.”

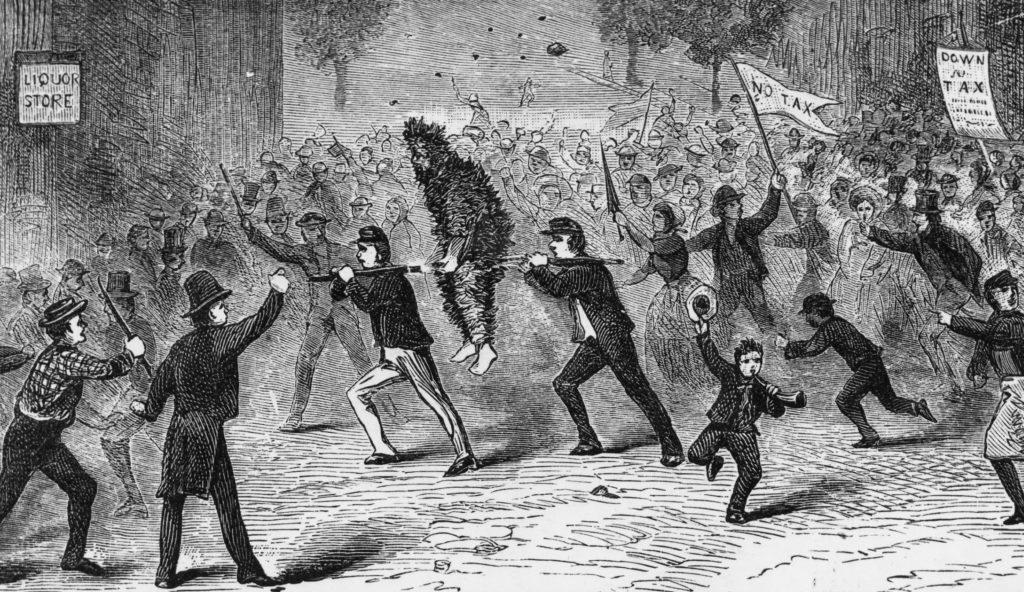

It was open season on excise tax collectors for the next two years. A farmer, hunter and small distiller named Daniel Hamilton (no relation to Alexander) was a ringleader of the violence. Hamilton had a reputation as a bully. His gang attacked tax collectors – and anyone who helped them – in all four counties. Their first victim was Robert Johnson. The mob cut his hair, then tarred and feathered him. When John Conor tried to serve warrants on Hamilton and his men for the attack, they whipped, tarred and feathered him. Then they blindfolded him and tied him up in the woods. Thorough men, they also didn’t forget to rob him of his horse and his money.

Many similar attacks took place over the next two years. The rebels took vengeance on anyone who paid their tax. A man who complied with the tax law was likely to have his barn burned or his still damaged. Men were also attacked merely for renting offices to the tax collectors. Tarring and feathering, destruction of property and whippings were meted out so diligently that the federal government soon had a hard time finding anyone to take the job of tax collector.

Oliver Miller and John Neville

One gentleman who was not afraid to enforce the tax was John Neville, a wealthy landowner (and slaveholder) in present-day Scott Township and Bridgeville. Neville had a large distilling operation and it was in his economic self-interest to see the small distillers put out of business by the tax. (See a little more about Neville in this previous post)

On July 15, 1794, Neville brought U.S. Marshal David Lenox to the property of William Miller. Their purpose was to serve a writ on Miller, fining him $250 for operating an unregistered whiskey still. Miller was required to appear in court in Philadelphia. For a frontier farmer, the travel was almost as great a hardship as the $250 fine. William, who had already sold off part of his farm and was planning to move to Kentucky, refused to accept the writ. Other nearby farmers heard the argument and fired shots at Neville and Lenox, forcing them to depart.

The next day, William Miller and 30-40 other farmers marched on Neville’s home, Bower Hill. Their goal was to capture Lenox, the U.S. Marshal, who they believed was at Bower Hill with Neville. Oliver Miller, a relative of William’s, was wounded in the skirmish that followed. The rebels retreated to another old fort, Couch’s Fort (near present-day South Hills Village) to gather reinforcements. By the next day, more than 500 men had gathered. They were led by a Revolutionary War veteran, Captain James McFarlane. And they were mad.

Park Two of the Whiskey Rebellion coming soon!

Sources

Bradford House Historical Association; The Bradford House: A National Historic Landmark; Washington, PA; 2015

Lorant, Stefan; Pittsburgh, The Story of an American City; Lenox, MA, Authors Edition, Inc.; Fourth Edition, 1988

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Whiskey_Rebellion

http://www.maptherebellion.com/neatline/show/the-whiskey-rebellion#records/10

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/David_Bradford_(lawyer)

Thank you for this informative article (and the second article in the series that finishes the story). Is there a place in Washington County where Hamilton’s portrait is still upside down?

Yes Hamilton is still upside down at Liberty Pole Spirits, 68 W. Maiden St., Washington, PA!

Thanks very much!