In this time of plague, it seems fitting to remember how people survived past calamities. And we are approaching the anniversary of a great local catastrophe: the Pittsburgh fire of 1845, a turning point in my upcoming novel Righteous.

Pittsburgh’s great fire is almost forgotten now, but for many years, the city commemorated the date by ringing out 1 – 8 – 4 – 5 on the old City Hall bell at noon on the anniversary, April 10. Articles about the fire appeared regularly in newspapers on the anniversary date, major ones appearing on the 25th anniversary in 1870, and following the similarly-devastating flood in 1936.

Origin of the Fire

Whenever there was a fire in a major city in the 19th century, some poor Irish woman always seemed to get the blame. But the story of Mrs. O’Leary’s cow in Chicago turned out to be apocryphal, and the origin story of the Pittsburgh fire is also in doubt. The story goes that the fire was started by Ann Brooks, an Irish washerwoman who worked for Colonel William Diehl on Ferry Street (present-day Stanwix Street). Mrs. Brooks was said to have started a fire to heat water for Col. Diehl’s laundry. She left it unattended and a spark ignited a nearby ice shed.

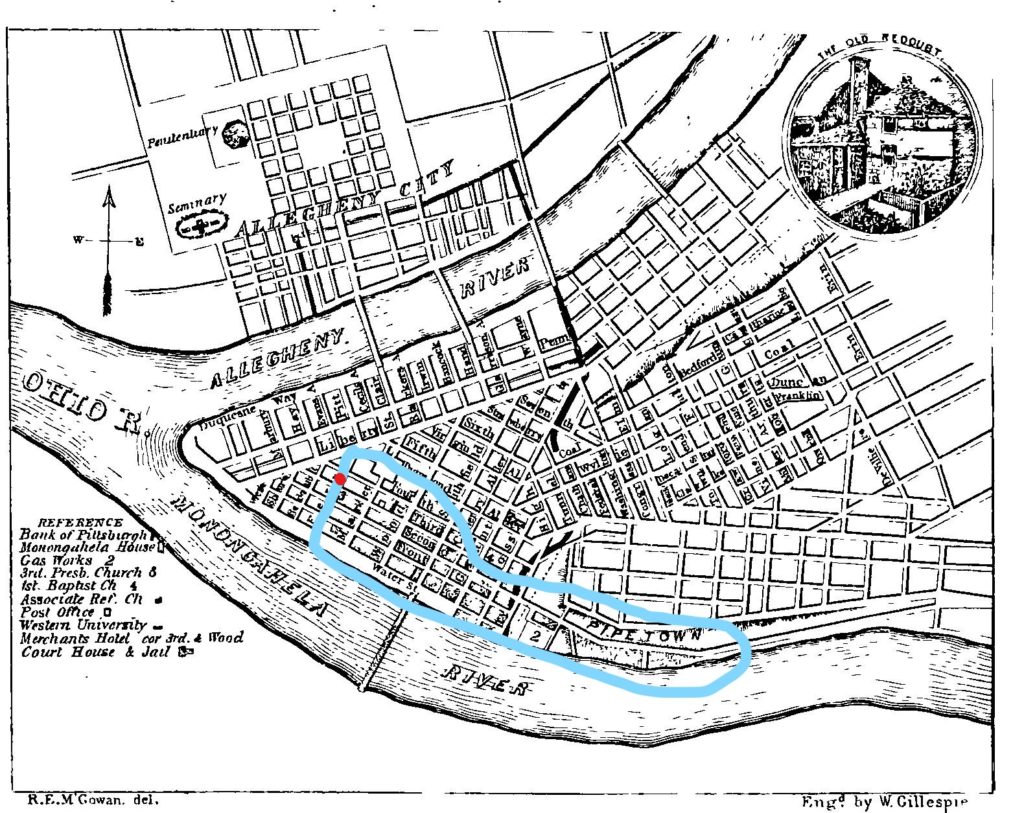

We don’t know whether Mrs. Brooks was really to blame, but it is undisputed that the fire started somewhere near the corner of Ferry and Second Streets and that it destroyed 60 acres, about 1/3 of the young city. Estimates of the total damage range from $6 million to $20 million. The best estimate is about $12 million, or $267 million in 2020 dollars.

Pittsburgh’s Preparedness (or not)

Also undisputed is that the city of Pittsburgh was as unprepared for the 1845 fire as our nation has been for the current pandemic. In 1844, the city built a new reservoir on Bedford Avenue to replace the old one that stood at the current location of the Frick Building. But the water mains and pumps were inadequate, leading to poor water pressure. The city had no municipal fire department. Six competing volunteer fire companies provided protection. They were well-intentioned but very poorly trained and equipped.

Conditions were against the city, too. Houses and businesses stood shoulder to shoulder, and the air was thick with flour dust, coal dust, soot and cotton fibers from the city’s many mills and factories. Sources say that no rain had fallen in anywhere from 2 to 6 weeks. 6 weeks of no rain in a Pittsburgh spring seems implausible, but all sources agree that it had been a dry spring and the reservoir was very low.

The fire spreads

The day of the fire was warm and windy.

A volunteer fire company arrived on Ferry Street soon after the ice shed fire was reported, but by then the flames had spread to the nearby Globe Cotton factory. Still, the fire could have been controlled at that point had the fire fighters not been hampered by low water pressure and their own rotted hoses

The fire raced up Second and Third, nearly destroying Third Presbyterian Church. The wooden spire of the church caught fire and the church was only saved by fire fighters cutting off the spire and letting it drop to the street.

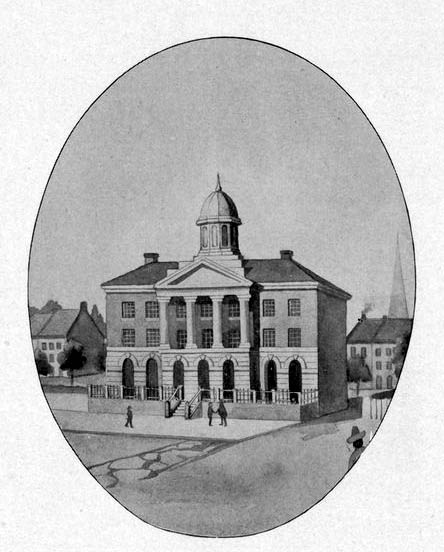

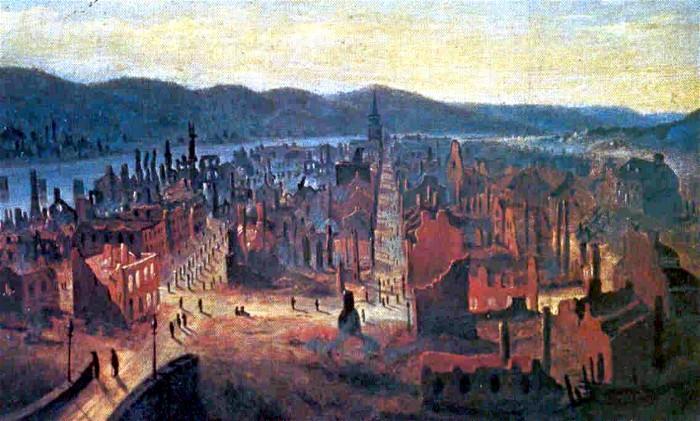

The flames reached their peak in Pittsburgh’s first and second wards between 2 and 4 p.m. Winds blew the fire south and east, destroying the city’s pride and joy, the elegant Monongahela House Hotel, as well as the Courthouse and Western University, predecessor to the University of Pittsburgh. The wooden Monongahela Bridge also burned, to be replaced by the first Smithfield Street Bridge.

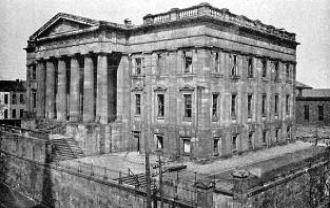

Bank of Pittsburgh

The Bank of Pittsburgh, built entirely of stone and metal, was supposed to be fireproof. The head cashier calmly locked the bank’s cash, books and records in the vault before vacating the building and standing on the street with other onlookers. When the building’s zinc roof melted, the interior burst into flames and was entirely gutted. The vault itself was fireproof, and the bank’s valuables remained intact, but the destruction of the building caused panic. People who had been merely observing the fire rushed home to try to save their possessions. Soon, carts full of boxes, furniture and other property clogged the chaotic streets. Most of these goods ended up abandoned, and either burned or stolen. Some people escaped across the Monongahela Bridge before it burned. Some fled northeast to the present-day Hill District, and courageous ferry operators transported many others to safety.

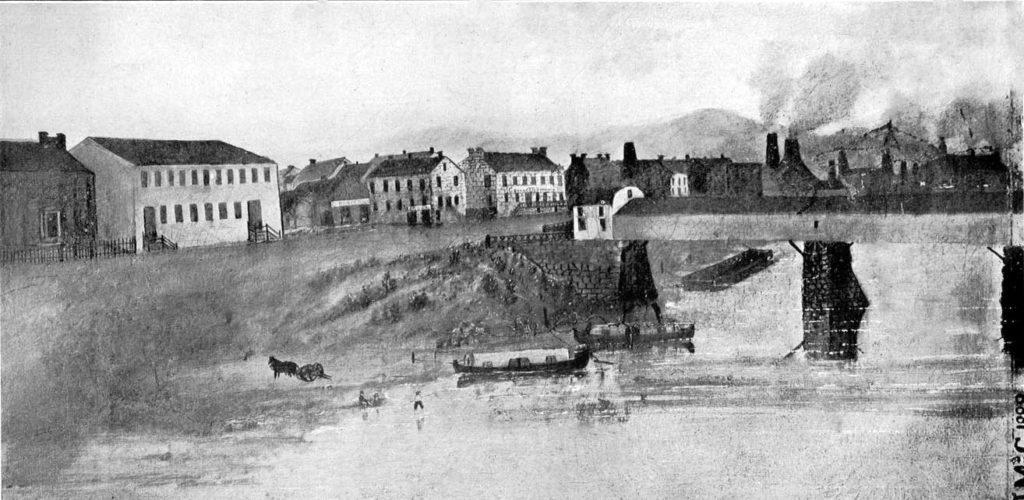

Destruction of wharf and Pipetown.

The flames raced along the Monongahela Wharf, destroying the docks, the warehouses and any boats that hadn’t cast off down the river in time. The destruction at the docks might have been contained if a barrel of liquor hadn’t fallen and burst right in the path of the flames, igniting nearby straw and the rest of the liquor warehouse.

The fire followed the Monongahela River towards Pipetown, an industrial suburb that lay below what was then called Boyd’s Hill (now called simply The Bluff, the present-day home of Duquesne University). There it randomly spared many factories while destroying others, including the city gas works, Miller & Co. glass works, and Dallas Iron Works. Finally, around 6 in the evening the winds died down, and by 7 p.m. the fire had burned itself out on the slope of Boyd’s Hill.

Cost of the catastrophe

The fire destroyed 10-12,000 buildings, displacing 2000 families, or about 12,000 people. A sampling of the businesses burned to the ground include the offices of the Daily Chronicle newspaper, the garage and all equipment of the Vigilant Fire Co., the Weyman Tobacco Factory, six drugstores, 4 hardware stores, 5 dry goods stores, 2 book shops, 2 paper warehouses, 5 shoes stores and 3 livery stables. Every insurance company in the city except one was bankrupted.

Incredibly, only two people died in the fire – out of a population of about 20,000. Lawyer Samuel Kingston returned to his house on 2nd St. to rescue his piano. He fell into the basement of his house, was trapped there and died. A Mrs. Maglone or Malone was also reported missing the day of the fire, last seen at a shop on 2nd St. A set of bones found in a store at the corner of 2nd and Grant on April 22 were believed to be hers.

Recovery

Pittsburgh rose from its ashes almost immediately. The state provided a moratorium on state taxes and $50,000 in relief ($1.7 million in today’s dollars). Donations came from other parts of the country and all over the world. Individual contributions of note include $500 from future president James Buchanan, $25 from future Secretary of War Edwin Stanton and $50 from former president John Quincy Adams. The city of Wheeling, WV, contributed 100 pounds of flour and 300 pounds of bacon.

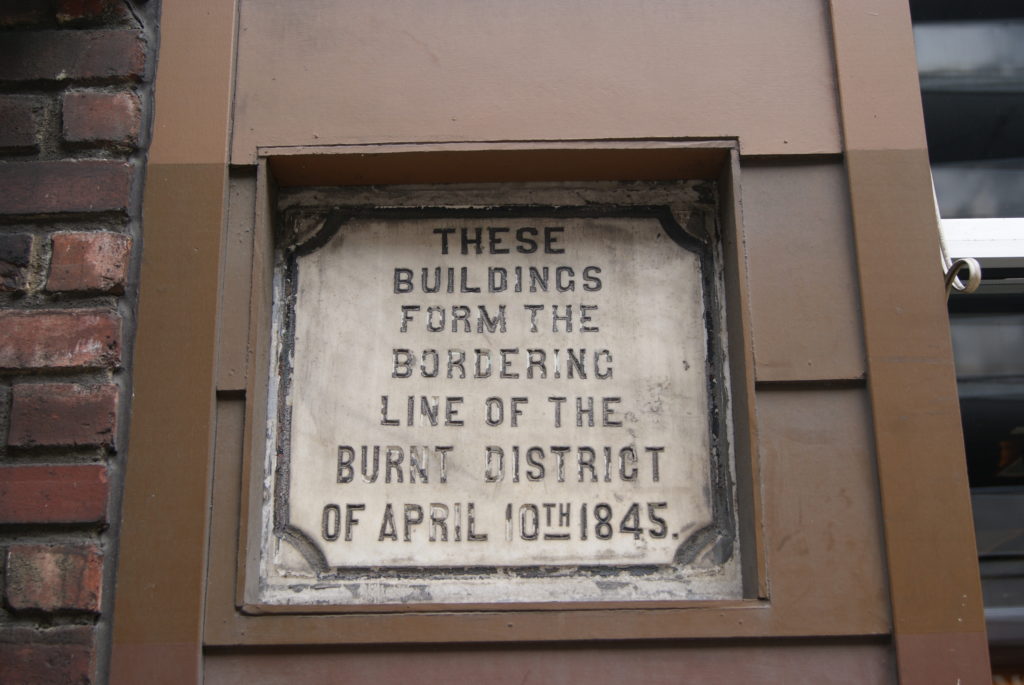

Property values skyrocketed, and a construction boom started on April 14, only 4 days after the fire. By June 12, while many streets were still blocked with fire debris, 500 new buildings were either completed or in progress. Fine buildings of brick or stone replaced the destroyed wooden tenements.

Pittsburgh came back from the great fire bigger and better. I have faith that we will emerge from our current calamity renewed, refined and strengthened.

And an aside…

A tidbit about the Monongahela House that I can’t bear to leave out, but that didn’t fit into the flow of my overall fire narrative: Presidents Lincoln, Garfield and McKinley all stayed at the rebuilt Monongahela House in the years following the fire. Garfield and McKinley slept in the same bed that Lincoln had used – and all three men were assassinated! The furniture from the “Lincoln Room,” including the unlucky bed, passed into the hands of Allegheny County when the Monongahela House was torn down in 1935. The County placed the furniture in a small museum on the grounds of South Park. The furniture was subsequently stored in a warehouse in South Park, where it didn’t come to light again until 2006. The bed is now in the possession of the Heinz Pittsburgh History Center.

Sources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Fire_of_Pittsburgh

http://www.steelcactus.com/PGHFIRST_1.html

My friend and former work colleague, Gary Link, has written a series of novels that take place in mid-19th-century Pittsburgh. The Pittsburgh fire is the central event of the first book in the series, The Burnt District:

Hi Kathryn, I was going through the reviews for the Passion of the Western Mind stopped to inquire as to the person behind the short sweet commentary! My ASK THE AUTHOR question: Health experts warn us about being sedentary for too long but as writers we often find ourselves seated for long hours. What are some brief ways to exercise the body regularly throughout the day without losing the writer s flow?

I love exercise almost as much as I love words, so this is an easy question for me. I take a walk outdoors every single day, unless weather absolutely forbids it. I also take a yoga break at some point during the day. I agree with you that exercise is important for both physical and mental healthy.

A Midwife s Tale: The Life of Martha Ballard, Based on Her Diary, 1785-1812 by Laurel Thatcher Ulrich David wrote: “Nicely said, Kathryn, about the “appropriation” issue. I agree with your premise that fiction is about placing yourself in another’s